The church of St Michael lies to the south of North Cadbury village, adjacent to North Cadbury Court (late 16th C). The church has many fascinating aspects. I have chosen three elements to see where they lead in terms of the church’s history. I visited the exterior of this church on the week that Prince Philip has died (April 2021). Hence the flag at half-mast. I was unable at that time to visit the interior of the church due to the Pandemic restrictions. The bench end and tomb monument photos were from a visit back in the summer of 2014.

There is some symmetry in this church – this is the south side of the church (the main photograph is of the north)

The architecture dates mostly from 1417. There are earlier elements – the tower is pre-1407. John Norton replaced the roof in 1866 and added the reredos.[i] The stone is Lias with Doulting stone dressings.[ii]

The founding of the new church (as St Michael’s) started in 1417. It was to become a collegiate church, initiated by Lady Elizabeth de Botreaux. In 1423 a royal license was granted to covert the parish church of North Cadbury into a college of seven chaplains and four clerks. By 1548 the benefice was ‘commonly callyd a college and hathe ben tyme out of mynde.’ [x]

It is unusual to have a collegiate church on this grand scale in Somerset. Usually, wealthy families would have a chantry chapel built on to a significant church. It survived as a college until the Reformation. However, it never had the intended 7 chaplains and 4 clerks.[iii] I wonder if this is because initially not that many priests would be needed to sing in perpetuity for the founders of the church. The increase in number would be needed for successive generations, which did not occur. Perhaps it started to return to a parish church for practical reasons over the subsequent decades.

The doctrine of Purgatory became a central theme developed in the 12th C. The concept of the perpetual chantry reached full maturity by 1230 (i.e., the singing in perpetuity for the souls of the dead, with the principal responsibility being towards the founders). The singing of masses for the dead helped to move their soul through Purgatory. Shifting from a function of the monasteries to the chantry chapels of the parish, the practice in effect became privatised.

Founder Tomb

The original tomb was situated on the chancel steps. Lord de Botreaux had died in 1391 before the rebuilding of the church. His wife, Lady Elizabeth, died in 1433.[iv] Her grandson, 3rd Baron Botreaux fought alongside Henry V at the Siege of Harfleur and then Agincourt in 1415, when he was 26. The rebuilding of the church may have further significance with the safe return of her grandson after the English victory at Agincourt. Her son (the 2nd Baron Botreaux) had died in 1395.[v] It is a bit confusing as to whom the tomb was for, as the barons and their wives have the same names (William and Elizabeth) but this is possibly meant as the 1st baron and his wife as she appears to be the driving force behind the collegiate church.

Tomb monuments are fascinating for many reasons. They inform us about a number of aspects – wealth, status, form, ornamentation, architecture, materials, costume, armour, political affiliations, interests and belief.

The tomb chest is carved with angel weepers under a foliage frieze. The vaulted canopy above the couple’s heads sits rather incongruously and is thought to have been placed there later.[vi] The canopy is present in a drawing of the tomb from 1890 (see below).

Carved Doulting Stone lying on what appears a Lias slab – but could be the lighting in my photo.

Image from book by W. H. Hamilton Rogers, F.S.A., The Strife of the Roses and Days of the Tudors in the West (1890). [vii]

The drawing from the book (1890s) shows the detail of the monument effigies. I find the Lady Elizabeth’s dress intriguing. Her hairstyle and horned-head dress are elaborate. She wears a double beaded necklace at her throat. Her robe and mantle are long with folds. There is a fastening arrangement of a tasselled cord that runs under her clasped hands. Her head rests of a lozenge-shaped cushion placed on a larger cushion. Notice the dog tooth frieze on the left of the knight.

Two supporting angels lie behind and down from her shoulders. Their hands and feet are visible.

Two dogs lie at Lady Elizabeth’s feet. One of them is wearing bells around its neck.

Beneath Lord William’s feet is a lion.

There is a fascinating account of the conservation of the tomb – follow this link:

https://www.yalhs.org.uk/1985-oct-pg61-62_a-mediaeval-table-tomb-the-conservators-tale/

FERRAMENTA – WINDOWS

With the large Perpendicular tracery windows of the chancel, one gets an idea of a collegiate church. This is a relatively large parish church for South Somerset. The 3-light windows have mullions are slender and shaped. They are relatively plain with cinquefoil cusping. The main cusps are supported by circular, internal ferramenta. There is no stained glass, although the glass looks like crown rather than plate. Did they originally have stained glass? The east window has stained glass from Clayton and Bell, dated 1876.[viii]

The external ferramenta is made up of iron stanchions running upwards through lugs in horizontal saddle bars.

The windows are placed high up in the chancel to allow for the choir stalls of the collegiate priests.

BENCH ENDS

The bench ends in the church are a fascinating collection of images. They date from 1538.[ix] It appears that there are different hands at work. Some of the carvings appear to have a lighter, almost comedic touch – a couple of snails (?) & a posing young man with a pack horse; a carver who liked lines – the buildings of the windmill and one of the church; another who enjoyed creating profiles of people (could they be locals?). Then there are the beasts – a crane and a unicorn (one of the beasts has a Renaissance flourish to it). The cat with the mouse and mousetrap has a simpler, homely and perhaps allegorical approach. There is also a turbaned man in profile. They are a curious collection and may be of different dates than one set.

I don’t know where this church is. On a hill perhaps relates to Devon or Cornwall? Maybe somewhere in the Somerset hills. Maybe relates to where the family who commissioned it comes from? It is detailed enough to suggest it is real place.

Some of the people of the North Cadbury parish perhaps? The two women kissing probably represents the kiss of peace.

The man appears to be playing a large flute (rather than perhaps a shawm, which would have a bell-like opening towards the end). His costume is rather fine and he stands confidently on a broken branch.

Madonna & Child – The child is quite adult-like which is usual for Christ in such imagery. With these bench ends possibly dating from circa 1538 it is right on the edge of change. The Dissolution of the Monasteries had started in 1536. The carving, of course, may have been a bit later under the reign of Mary I and therefore was never subject to the destruction of imagery in the parish church in the Reformation under Edward VI (r. 1547 to 1553).

It is different in style to the other bench ends of people. The carver has taken a great deal of time over the folds of the Madonna’s robe.

It is quite possible that the bench ends were carved at different times over the 16th C and into the 17th C.

St Margaret reading after she has emerged from the dragon. The dragon still has folds of her cloak in its mouth. Like the image of the Madonna above the carver has concentrated on producing voluminous folds of her cloak.

It makes me wonder whose bench end this would have been. Perhaps a warning to the young men of the parish. The young man wears a cod piece and puffed sleeves. His pose is arrogant and has a rather fancy, long whip-type instrument to drive his pack horse or ass.

Five wounds of Christ – 4 nails and the spear – with the crown of thorns and heart.

Snails, dragons emerging from eggs or tortoises?

A crane, heron or stork? In the medieval bestiary the crane was a icon of vigilance. Cranes and herons inhabit the Somerset Levels, not far from North Cadbury.

Cat, mouse and mouse trap

Unicorn or Yale presenting a shield. The unicorn’s horn has had be bent somewhat to fit into the bench end.

Renaissance-style flourish. Different carvers bring different designs. Probably as an individual you commission your own bench end.

What I haven’t looked at here is the positioning of the bench ends. They are relevant to the seating hierarchy of the congregation. Provided the benches are in the same place as they were originally, the imagery and position may provide some insights.

What is also worth noting is that the bench ends reflect the fact that the church has become a parish church. No longer a collegiate church for a family. When this transfer occurred is not clear. By the time the church was completed (maybe circa late 1420s?) it would be one hundred years or so until changes started to occur in terms of the collegiate church becoming decommissioned and officially being placed as the parish church.

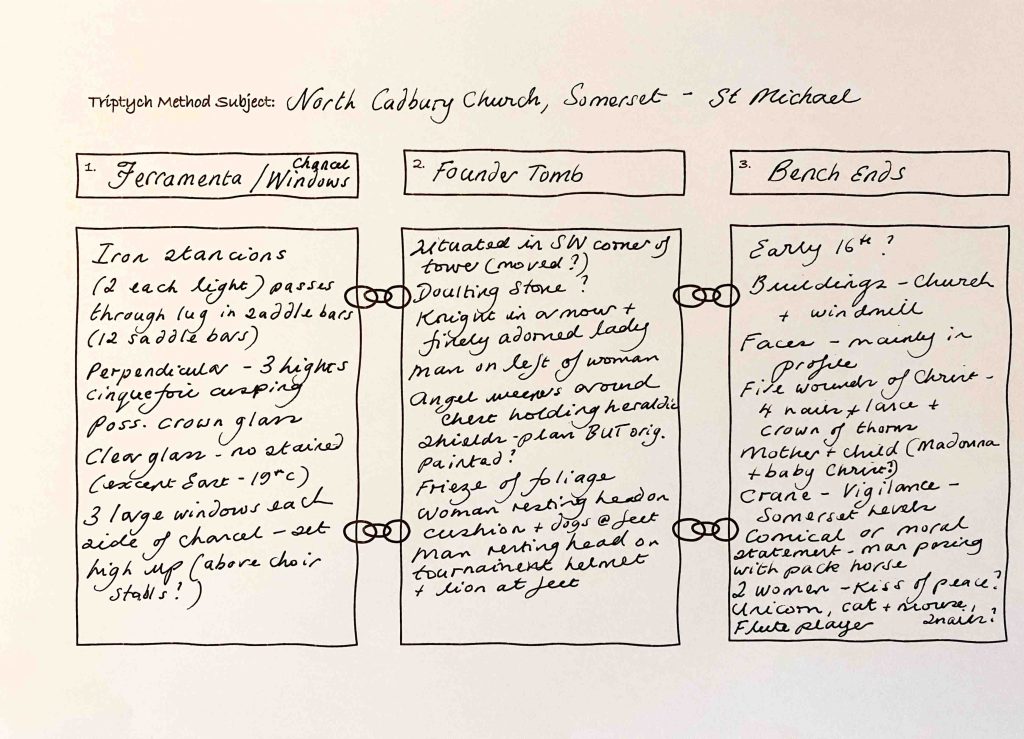

TRIPTYCH METHOD OF RESEARCH

I am trying out a methodology in approaching buildings – something I have created for my own purposes. Sometimes it is too easy to get overwhelmed in everything a building can offer. Sometimes there is only a limited amount of time to make a study. So, I have decided to approach analysis (particularly with churches) with a ‘triptych method’ – to take 3 elements and focus in on them. They are not necessarily related but can help in building up a picture without getting too analytical of the diversity of elements available. For North Cadbury Church the notes area as such:

The 3 elements are randomly chosen as things that piqued my interest at the time. Another time at the same church I could pick another 3.

NOTES

[i] Julian Orbach and Nikolaus Pevsner, Somerset: South and West (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014)

[ii] ‘Church of St Michael’, Historic England List Entry 1178133, (1961),

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1178133 [accessed 14 May 2021].

[iii] Orbach & Pevsner, p. 487.

[iv] Orbach & Pevsner, p. 487.

[v] Michael Wren, ‘William de Botreaux, 3rd Baron Botreaux’, The Worshipful Company of Bowyers, (2014), https://www.bowyers.com/agincourt_botreaux.php [accessed 14 May 2021].

[vi] Roger Harris, ‘A Medieval Table Tomb – The Conservator’s Tale’, Yeovil Archaeological and Local History Society, https://www.yalhs.org.uk/1985-oct-pg61-62_a-mediaeval-table-tomb-the-conservators-tale/ [accessed 14 May 2021].

[vii] W. H. Hamilton Rogers, F.S.A., The Strife of the Roses and Days of the Tudors in the West (Exeter: James G. Commin, 1890), p. 147 – Retreived from Project Gutenburg https://ia800307.us.archive.org/29/items/strifeofroses00rogeuoft/strifeofroses00rogeuoft.pdf[accessed 14 May 2021].

[viii] Orbach & Pevsner, p. 487.

[ix] Orbach & Pevsner, p. 487.

[x] ‘Colleges: North Cadbury’, in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1911), p. 161. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol2/p161a [accessed 18 May 2021].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

‘Colleges: North Cadbury’, in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1911), p. 161. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol2/p161a [accessed 18 May 2021]

Covin, H.A. (2000). “The Origin of Chantries”. Journal of Medieval History, 26, 163-173

‘Church of St Michael’, Historic England List Entry 1178133, (1961), https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1178133 [accessed 14 May 2021]

Hamilton Rogers, F.S.A., W.H., The Strife of the Roses and Days of the Tudors in the West (Exeter: James G. Commin, 1890), p. 147 – Retreived from Project Gutenburg https://ia800307.us.archive.org/29/items/strifeofroses00rogeuoft/strifeofroses00rogeuoft.pdf [accessed 14 May 2021]

Harris, Roger, ‘A Medieval Table Tomb – The Conservator’s Tale’, Yeovil Archaeological and Local History Society, https://www.yalhs.org.uk/1985-oct-pg61-62_a-mediaeval-table-tomb-the-conservators-tale/[accessed 14 May 2021]

Orbach, Julian and Nikolaus Pevsner, Somerset: South and West (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014)

Wren, Michael ‘William de Botreaux, 3rd Baron Botreaux’, The Worshipful Company of Bowyers, (2014), https://www.bowyers.com/agincourt_botreaux.php [accessed 14 May 2021]