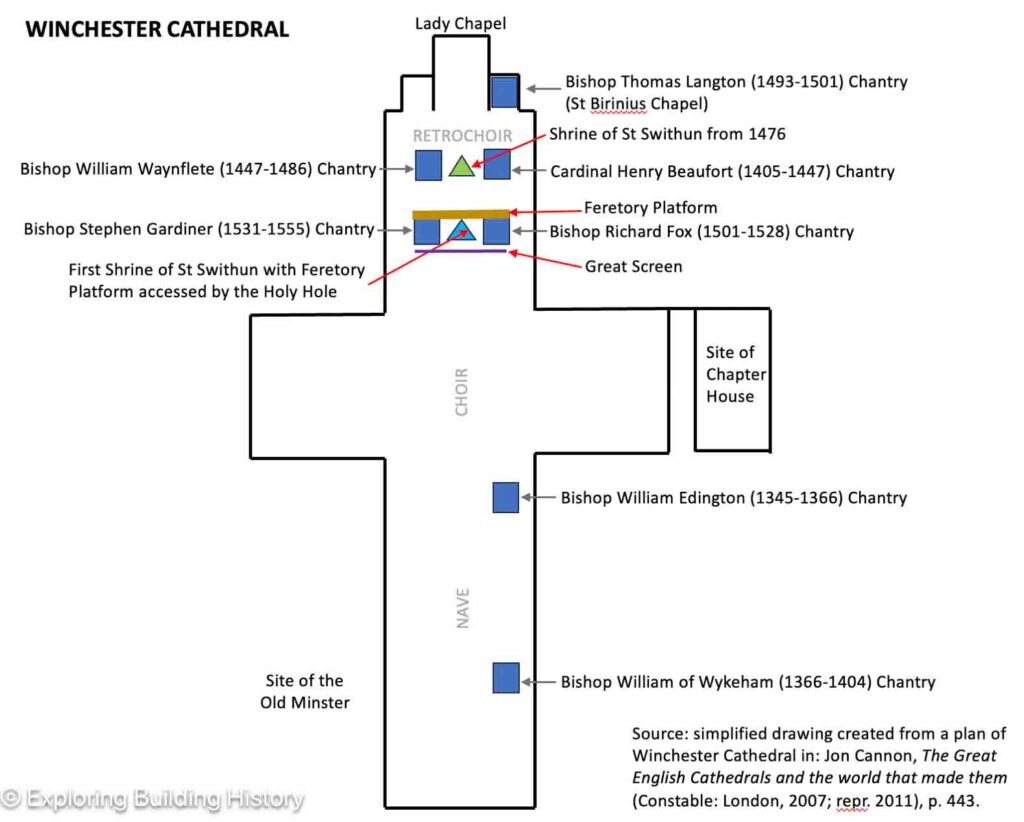

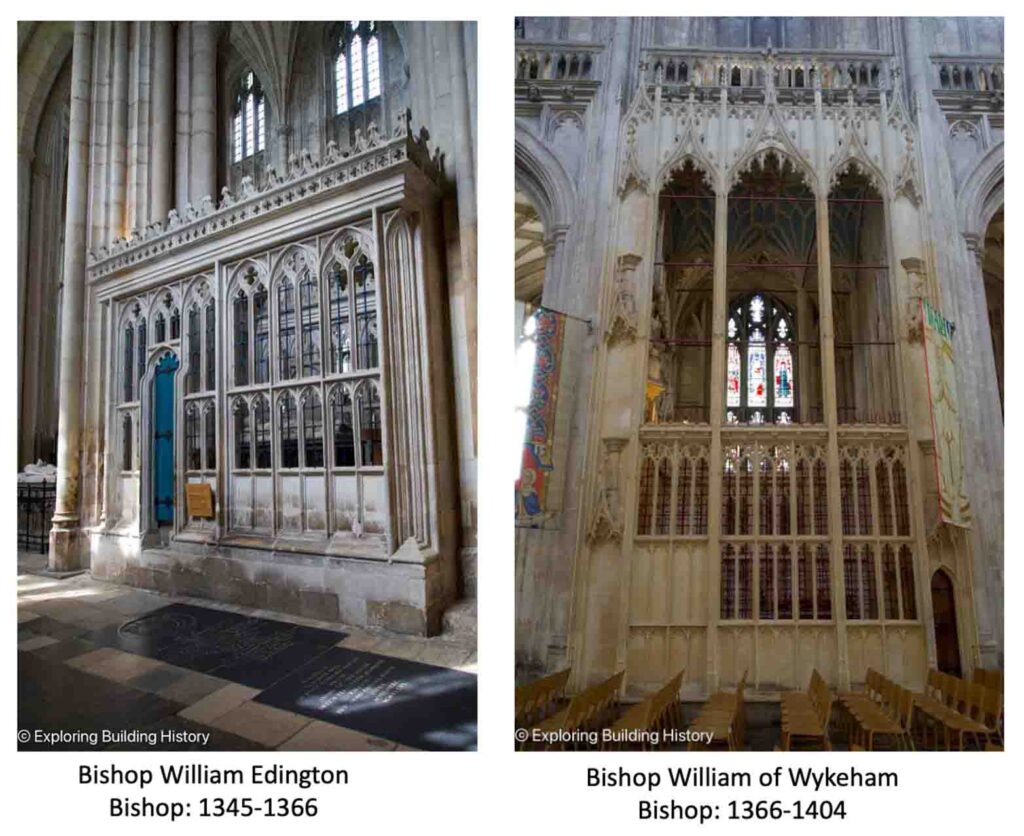

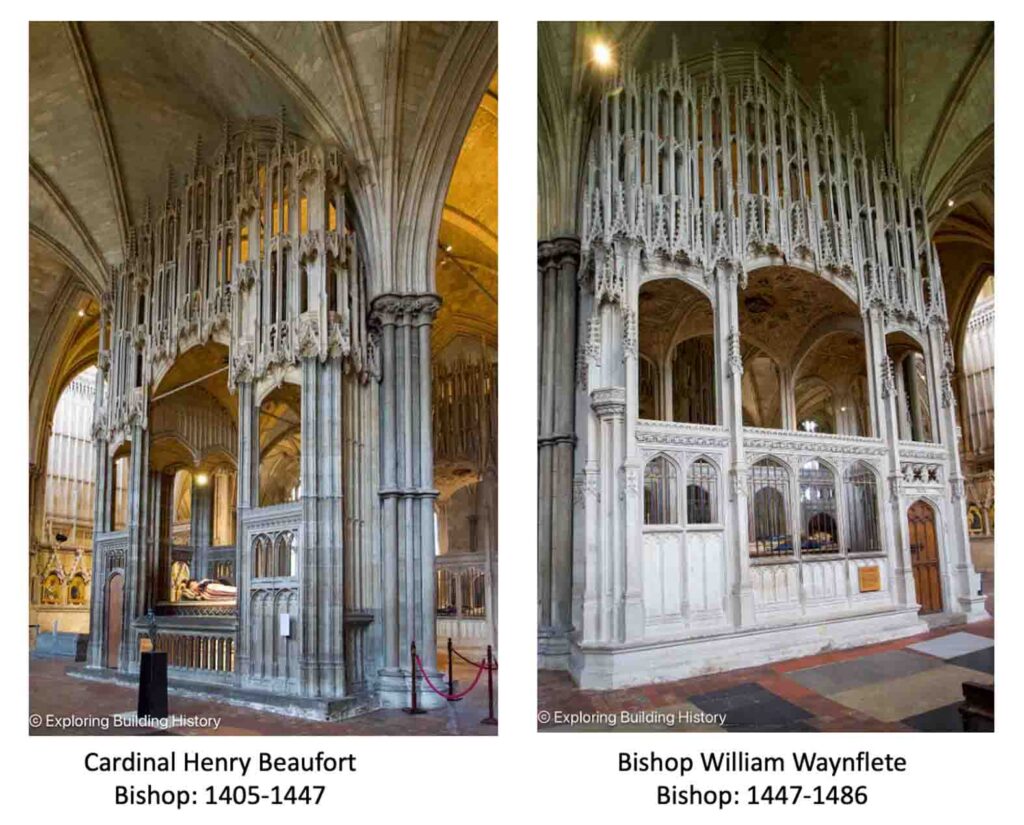

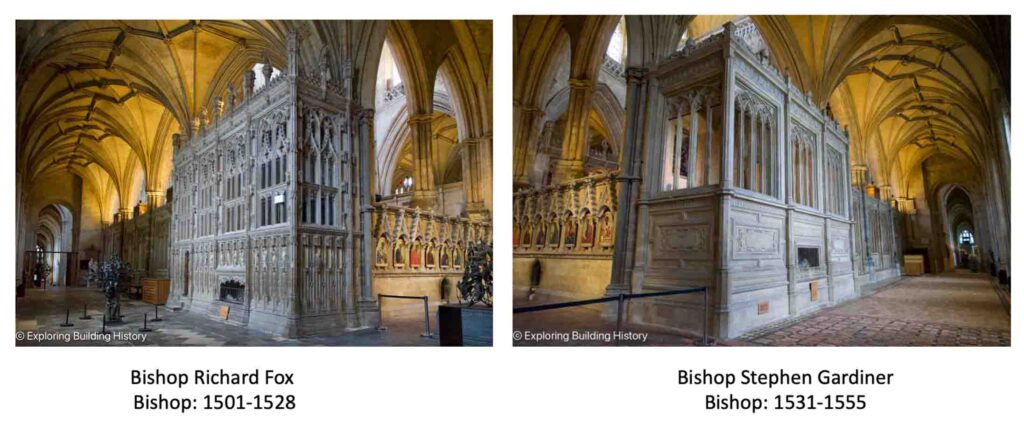

In Winchester Cathedral are six free-standing chantries dating from the mid-14th C to the mid-16th C. They provide an interesting comparison of Perpendicular micro-architecture over two hundred years, demonstrating the innovative and master accomplishment of medieval stone masons.

| Years as Bishop | Location of Chantry | ||

| 1 | William Edington | 1345-1366 | S side of Nave (east) |

| 2 | William of Wykeham | 1366-1404 | S side of Nave (midway) |

| 3 | Cardinal Henry Beaufort | 1405-1447 | S side of later position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 4 | William Waynflete | 1447-1486 | N side of later position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 5 | Richard Fox | 1501-1528 | S side of original position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 6 | Stephen Gardiner | 1531-1555 | N side of original position of St Swithin Shrine |

The ‘cage’ chantry was an innovation dating from the 1360s, developed by royal masons working at Winchester. The six cage chantries reflect the architectural expression of six different bishops in the context of their time. By the 1540s there were over forty of these structures in English cathedrals. The six at Winchester stand magnificently monumental to the powerful magnates that ran medieval England from the mid 14th C to the mid 15th C.[i]

The cage chantry could be placed like a booth in the cathedral, maybe slotting between two arcade piers in the nave or free standing in the retrochoir. Rather than taking up a side chapel or slotted in an aisle, or placed in the nave as a plain tomb, the bishop could reflect their own expression of magnificence without too much space. It seems they also survived the ravages of the Reformation, Civil War and Victorian reordering.

Position of the six cage chantries:

It the plan above is the chantry of Bishop Thomas Langton (d. 1501), which is contemporary with the 16th C chantries. However, it was created in an existing chapel and not one of the ‘cage’ types. Many chantries were side chapels.

The six free-standing cage chantries demonstrate the diversity in architecture from the mid 14th C to the mid 16th C.

- Mid 14th Century to Early 15th Century: Perpendicular Development for 2 Bishops who Pioneered a New Nave

- 15th Century: Bishop Waynflete’s Innovation: Two Chantries with Soaring Pinnacles & Fan Vaulting flanking the new Shrine of St Swithun

- 16th Century: Restraint, Memento Mori & Perpendicular with Renaissance motifs

NOTES ON CHANTRIES

The term ‘chantry’ comes from the Old French chanceries, meaning ‘to sing’.[i] A chantry priest would sing or say a mass for the soul of the dead as part of the doctrine of Purgatory. Eammon Duffy described Purgatory as ‘the out-patient department of Hell’.[ii] A place where repentant sinners were cleansed ready for Heaven. The doctrine of Purgatory had been established in the 12th C.

At the great Burgundian Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, the praying and masses for the dead was promoted from the 11th C. It was at the abbey under Abbot Odilon (994-1048) the date of November 2 as All Souls’ Day was instituted.[iii] This further developed into a liturgy for the dead to help them on their way through Purgatory. Henry of Blois, bishop at Winchester from 1129 to 1171 spent his early life as a monk at Cluny.

The origins of the chantry started in western Europe. With the established practice of prayers and masses for the dead the wealthy began to want a physical privatised altar or chapel. The chantry began to appear in France towards the end of the 12th C. England followed later, from the mid-13th C.[iv] Whilst the monks at Cluny had masses on All Souls’ Day for the general baptised dead, they also became hugely successful in chantry chapels, which were annexed to the abbey, working all the time for the souls who paid. This created significant wealth for the Cluniac order with an industry in masses sung for souls in perpetuity. The privatised singing or saying of masses for the dead moved on from a monastic function to chantries in the parish church.

The concept spread across western Europe with the system of endowment. The donor would endow the chantry and the payment for one or more priests. In the case of Cardinal (Bishop) Henry Beaufort, he left provision for 10,000 masses in his will along with the funding for his chantry.[v] A endowment could also pay for a relative or preferred individual to be established as a chantry priest. It had both a spiritual and temporal function.[vi] The chantry was a form of private salvation, The regular offering of the Eucharist in the mass was the most effective way for redemption and the chantry was a physical place where this could happen.[vii]

Chantries were for the wealthy individual but also guilds and fraternities provided endowments for their members at a more affordable level.[viii]

The Dissolution of the Chantries in 1537 (under Edward VI) implemented the confiscation of chantry endowments. This had a wider impact on social institutions. Chantry income could come from specific land or property rents. The investment also paid for charitable institutions such as schools, hospitals, and almshouses. This new legislation confirmed an official disapproval of Purgatory and negated the need for masses for the deceased. All chantry funds, income, and valuables (such as plate and vestments) were transferred to the Crown.[ix]

Chantries can be the free-standing booths or side chapels in cathedrals and parish churches. They can also be dedicated collegiate churches. At North Cadbury, in Somerset a royal license was granted in 1423 to convert the parish church into a college of seven chaplains and four clerks.[x]

NEXT BLOG POSTS

In the next sequence of blog posts the chantries will be looked at in more detail.

NOTES

[i] Stephen Friar, The Companion to Cathedrals & Abbeys (Stroud: The History Press, 2010; repr. 2011), p.60.

[ii] Friar, pp. 112-3.

[iii] ‘History of the Abbey of Cluny’, Abbaye de Cluny, < https://www.cluny-abbaye.fr/en/discover/history-of-the-abbey-of-cluny> [accessed 26 August 2025].

[iv] K. L. Wood-Legh, “Some Aspects of the History of Chantries in the Later Middle Ages.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 28, 1946, pp. 47–60. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3678623 [accessed 24 August 2025].

[v] G. L. Harriss, “Beaufort, Henry [called the Cardinal of England] (1375?–1447), bishop of Winchester and cardinal.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 03, 2008. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1859 [Accessed 24 Aug. 2025].

[vi] K. L. Wood-Legh, “Some Aspects of the History of Chantries in the Later Middle Ages”, p. 50.

[vii] Friar, pp. 60-62.

[viii] Friar, pp. 60-62.

[ix] Friar, pp. 60-62.

[x] ‘Colleges: North Cadbury’, in A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 2, ed. William Page (London, 1911), p. 161. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/som/vol2/p161a [accessed 18 May 2021].

[i] Jon Cannon, The Great English Cathedrals and the world that made them (Constable: London, 2007; repr. 2011), p. 137.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cannon, Jon, The Great English Cathedrals and the world that made them (Constable: London, 2007; repr. 2011)

Friar, Stephen, The Companion to Cathedrals & Abbeys (Stroud: The History Press, 2010; repr. 2011)

Harriss, G. L. “Beaufort, Henry [called the Cardinal of England] (1375?–1447), bishop of Winchester and cardinal.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 03, 2008. Oxford University Press. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-1859 [accessed 24 August 2025].

Wood-Legh, K. L, “Some Aspects of the History of Chantries in the Later Middle Ages.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, vol. 28, 1946, pp. 47–60. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3678623, [accessed 24 August 2025]