To describe the architecture of a cathedral is a significant task and perhaps ends up as dry facts. At Winchester the magnificent nave, choir, chancel or sanctuary are a wonder to behold and experiencing the space is an aim in itself.

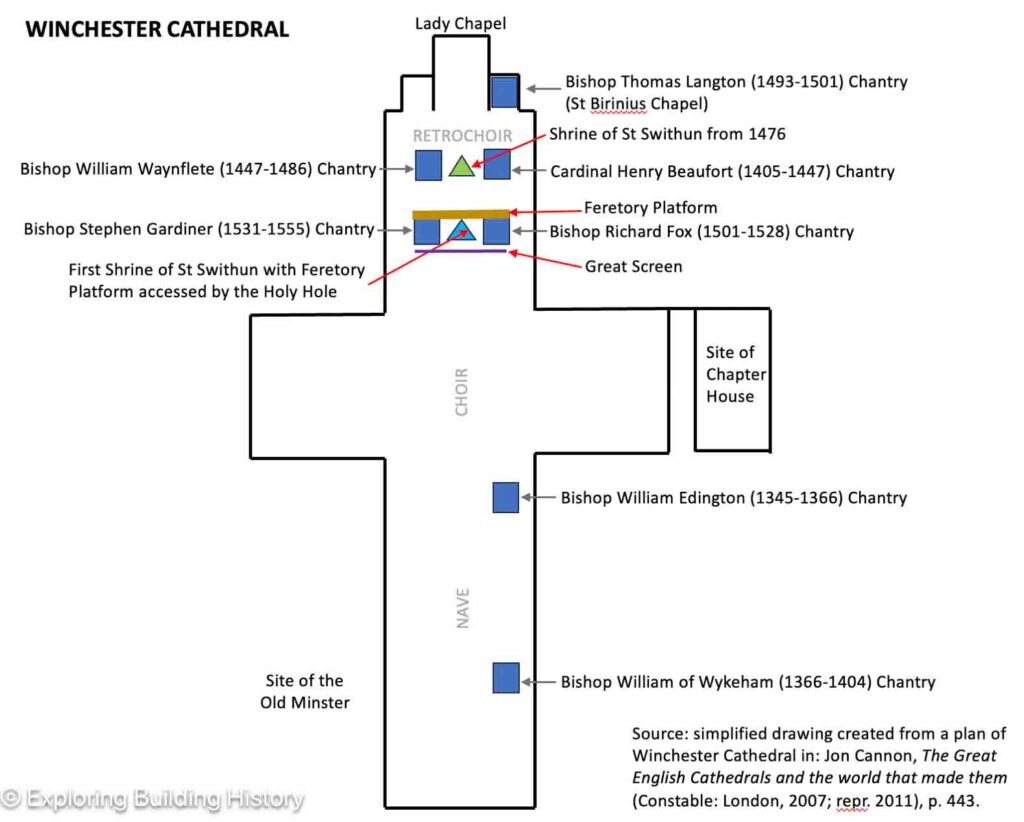

What I thought perhaps to bring to mind are the chantry chapels of bishops of Winchester. They have their own micro architecture and relate directly to those who shaped the cathedral’s history. The seven key Winchester chantry chapels date from the mid-14th C to the mid-15th C.

| Years as Bishop | Location of Chantry | ||

| 1 | William Edington | 1345-1366 | S side of Nave (east) |

| 2 | William of Wykeham | 1366-1404 | S side of Nave (midway) |

| 3 | Cardinal Henry Beaufort | 1405-1447 | S side of later position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 4 | William Waynflete | 1447-1486 | N side of later position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 5 | Thomas Langton | 1493-1501 | S side of Lady Chapel (St Birinus Chapel) |

| 6 | Richard Fox | 1501-1528 | S side of original position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 7 | Stephen Gardiner | 1531-1555 | N side of original position of St Swithin Shrine |

But before examining them I wanted to identify the location of the majority in the retrochoir.

WINCHESTER CATHEDRAL LAYOUT OF CHANTRIES

Below is a plan relative to the discussion in this blog post.

WINCHESTER RETROCHOIR: Beyond the High Altar & Great Screen

At Winchester the majority are clustered in the region of the retrochoir. The retrochoir is an area to the east of choir and presbytery. At Winchester the eastern end of the church was extended in the 13th C to create a resplendent vaulted hall. This could accommodate the location of the shrine of St Swithin and visiting pilgrims. The shrine was moved in 1476, much later than the retrochoir extension of the 13th C.[i]

Note that there is an alternative definition of retrochoir in medieval monastic and secular churches, as being the space to the west of the choir between the pulpitum and rood screen.[ii]

PRESBYTERY, SANCTUARY & CHANCEL

The sanctuary is the part of a church where the high altar sits. To be correct the sanctuary sits within the presbytery. The sanctuary is often raised within the presbytery.[iii] The presbytery is the eastern area of a major church which, in the medieval period was reserved for ‘the place of the presbyters’ (i.e. the elders of the church). Following the Fourth Lateran Council of 1214, which established the Doctrine of Transubstantiation, the mystery of the Eucharist needed protection from the secular nave. In medieval churches the rood screen created this separation. This enclosed space is often called the chancel and the term presbytery wrongly applied to the sanctuary.[iv]

In medieval major monastic churches and cathedrals, it was the pulpitum, along with the rood screen which created the separation from the nave.[v] Eastwards behind the screens was presbytery, incorporating the choir and the sanctuary. The term chancel is relatively new, derived from the Latin cancelli, meaning ‘lattice’ or ‘grating’.[vi]

PERPENDICULAR CHANTRY CHAPELS THAT SURROUND THE SHRINE OF ST SWITHUN

The soaring perpendicular chantry chapels which surround the site of the 13th C shrine contain the following bishops of Winchester:[vii]

| Cardinal Henry Beaufort | 1405-1447 |

| William Waynflete | 1447-1486 |

| Richard Fox | 1501-1528 |

| Stephen Gardiner | 1531-1555 |

Shrine Position of 1476. Cardinal Beaufort’s Chantry on the left & Bishop Waynflete’s Chantry on the right. Medieval Tiled Pavement.

Shrine position of 1476 with Bishop Waynflete’s late 15th C Chantry behind. Before the Shrine is the Tomb of Bishop Godfrey, who extended the retrochoir in the 13th C.

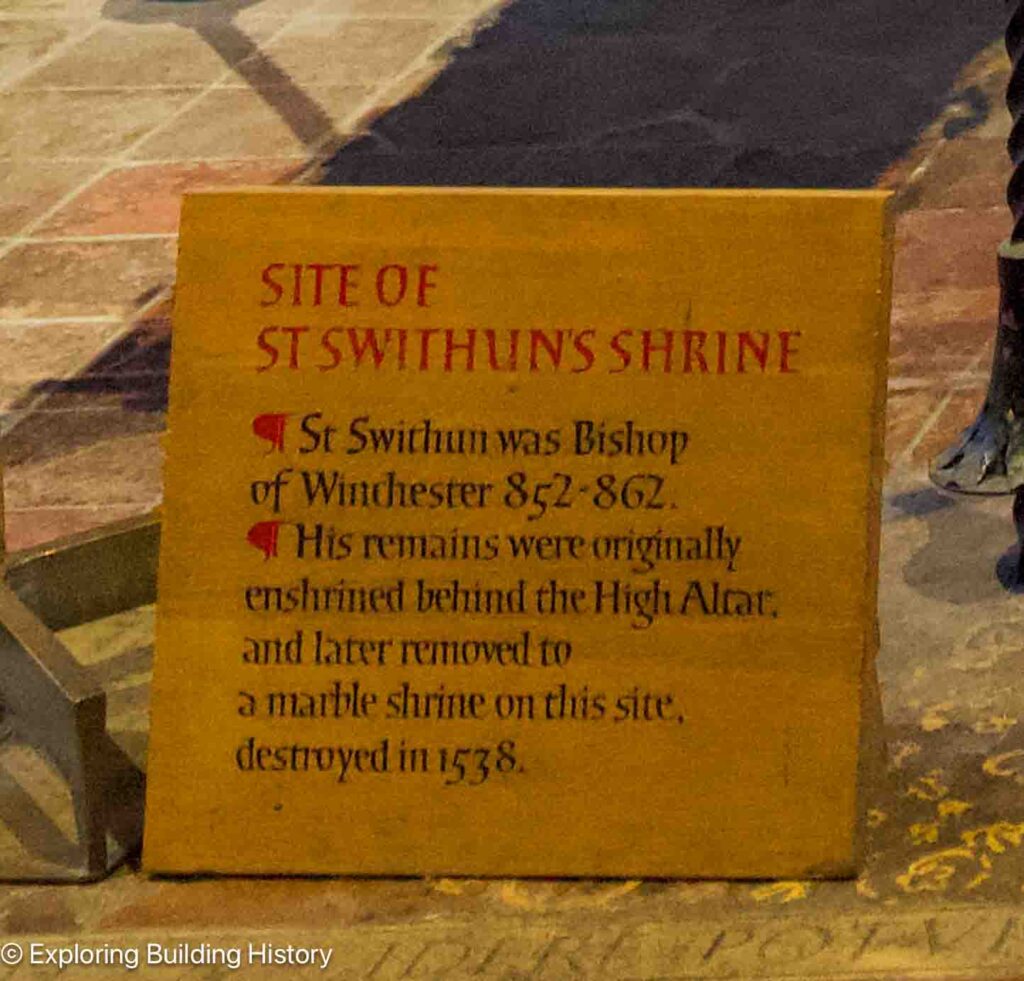

The retrochoir extension was begun by Bishop Godfrey de Lucy (1189-1204). His tomb sits in front of the site of St Swithun’s shrine (the east side), topped with a Purbeck marble slab. From 1476, St Swithun’s shrine was moved to this part of the cathedral. The shrine was demolished in 1538.[viii]

THE MEDIEVAL TILES

Winchester Cathedral has a wonderful pavement of medieval tiles in the retrochoir. These tiles date from the 13th C.[ix]

13th C Tiles

The 4 chantries that surround the shrine date from 1450 onwards.

SAINTS, ST SWITHUN’S SHRINE & THE ‘HOLY HOLE’

The row of icons behind were commissioned by the Cathedral’s Chapter in 1992. The were painted by Sergei Feyderov. They form a Deisis or Deesis, a traditional iconic representation with the central icon of Christ Pantocrator (or Christ in Majesty), enthroned and holding a book, flanked by the Virgin Mary and St John the Baptist. Then there are other saints and angels. Here from left to the Virgin Mary is St Birinus (Apostle to the West Saxons), St Peter, and the Archangel Gabriel. To the right of St John the Baptist, is the Archangel Michael, St Paul and St Swithin.[x]

![]()

SAINT BIRINUS (Apostle to the West Saxons)

St Birinus

St Birinus: A 7th C Italian monk (d. 650) came to England to assist with the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. He had been consecrated bishop in Milan before he arrived. In 635 he baptised King Cynegils, with King Oswald of Northumbria standing as godfather. The kings granted him land at Dorchester-on-Thames to establish his episcopal see and cathedral church. He became the first bishop of the West Saxons. His relics came to Winchester, although the 13th C Augustinian Canons at Dorchester claimed to possess them.[xi]

SAINT SWITHUN & THE HOLY HOLE

St Swithun

St Swithun’s Shrine location looking east towards the Lady Chapel.

The shrine memorial dates from 1962[xii]

Below the row of icons is the ‘Holy Hole’. It was a way for pilgrims to access the original shrine which was just behind the Great Screen, keeping a separation from them and the monastic church of the Benedictine community. The pilgrims would crawl into the Holy Hole to get access to the reliquary shrine of St Swithin. The pilgrim visit arrangement was established by Bishop Henry of Blois in the 1150s. The remains of St Swithun were displayed on a ‘feretory platform’ behind the high altar. They would crawl beneath the platform with the St Swithun’s relics resting above.[xiii] The icons replace polychrome figures of early Saxon royalty and bishops. They were destroyed in the Reformation in the mid-16th C.[xiv]

SUMMARY

Winchester Cathedral has evolved in a way that does not forget its Anglo-Saxon connection but developed a magnificence for its medieval bishops and pilgrimage site. The retrochoir must have been an amazing wonder of the medieval world. An experience that would have struck awe into the dusty-footed pilgrim as they walked over the medieval pavement and looked up at early English stone vaults and soaring perpendicular chantries.

NOTES

[i] Warwick Rodwell, The Archaeology of Churches (Stroud: Amberley, 2012), p. 9.

[ii] Stephen Friar, The Companion to Cathedrals & Abbeys (Stroud: The History Press, 2010; repr. 2011), p. 326.

[iii] Friar, p. 338.

[iv] Friar, p. 302.

[v] Friar, p. 304.

[vi] Friar, p. 59.

[vii] Friar, p. 326.

[viii] John Crook, Winchester Cathedral (Andover: Pitkin, 1990; repr. 1996), p. 9.

[ix] Crook, p. 9.

[x] Tim Manners Smith, ‘Winchester Icons’, British Association of Iconography 2019 https://www.bai.org.uk/winchester-icons/[accessed 12 July 2025].

[xi] ‘St Birinius Story’, Dorchester Abbey < https://www.dorchester-abbey.org.uk/st-birinus-story/> [accessed 30 July 2025].

[xii] Crook, p. 9.

[xiii] Crook, p. 9.

[xiv] Manners Smith, ‘Winchester Icons’.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cannon, Jon, The Great English Cathedrals and the world that made them (Constable: London, 2007; repr. 2011)

Crook, John, Winchester Cathedral (Andover: Pitkin, 1990; repr. 1996)

Friar, Stephen, The Companion to Cathedrals & Abbeys (Stroud: The History Press, 2010; repr. 2011)

Manners Smith, Tim, ‘Winchester Icons’, British Association of Iconography 2019 https://www.bai.org.uk/winchester-icons/ [accessed 12 July 2025]

Rodwell, Warwick, The Archaeology of Churches (Stroud: Amberley, 2012)

‘St Birinius Story’, Dorchester Abbey < https://www.dorchester-abbey.org.uk/st-birinus-story/> [accessed 30 July 2025]