The church of St. Cuthbert in Wells contains a remarkable carved oak pulpit of 1636. Its degree of craftsmanship and intriguing subject matter make it a standout piece of 17th century woodwork.

The Jacobean period (c. 1603-1625) extends in terms of style into the mid 17th century. It is characterised with a focus on symmetry and proportion with geometric and Renaissance patterns containing the decoration of intriguing subjects such as figures, mythical creatures, fruit, animals and symbols. Somerset has a tradition of bench ends, dating from the 16th and into the 17th century, which lent themselves to Jacobean styles, as seen in the later ones.

The expression of decoration in woodwork linked to powerful patronage, skilled craftsmanship and religious identity. This was a time of post-Reformation, which had upturned the traditional Catholic religion, creating a new Protestant religion. The rise of Puritanism was followed by the Laudian counter-reform bringing a High-Church approach. The religious politics and ideas along with the rise of a wealthy merchant class, particularly in woollen cloth, gave rise to new patrons of church furnishings, not always in line with the ecclesiastical hierarchy authority.

St. Cuthbert’s was the only parish church at the time in the cathedral city of Wells, standing around 500 yards from the Cathedral and Bishop’s Palace.[i] The other parish church of St. Thomas in the city was built in the 1850s. In St. Cuthbert’s is a curious carved pulpit of 1636. The date plate has not survived but was described by Thomas Holmes in 1908.[ii] Like much of this period’s woodwork it is executed in oak, and demonstrates the skill of the wood carver, and their imagination. Such carving was often left unpainted, as the decoration was the expression. On some grander schemes gilding and paintwork did appear.

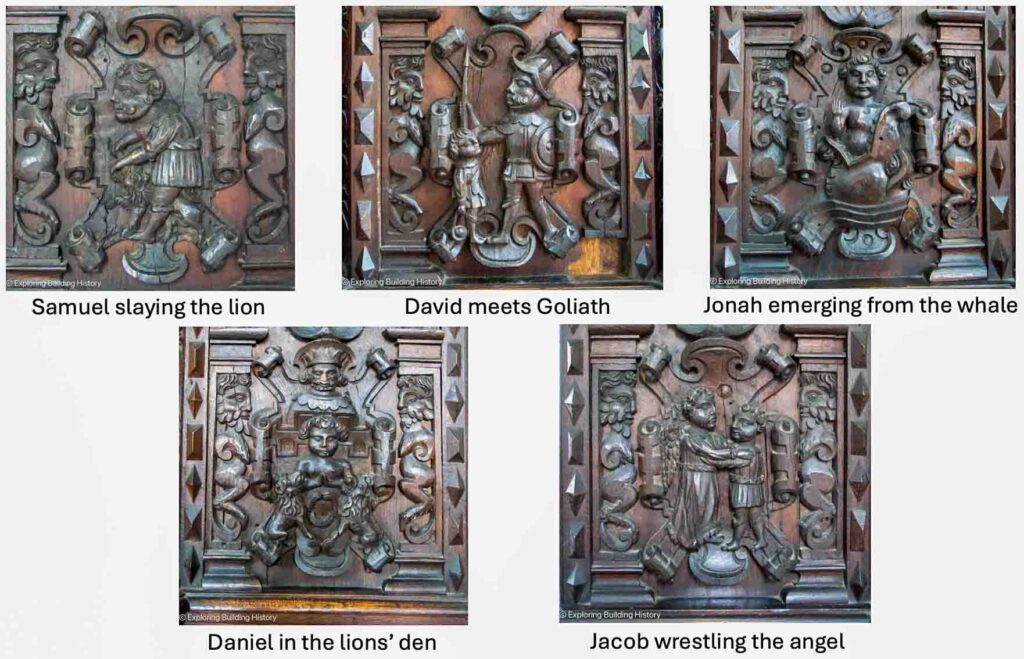

The hexagonal pulpit has five panels with Old Testament scenes. There may have been a door to the pulpit on the sixth side.[iii] The Old Testament scenes depicted are as follows:[iv]

(a) David meeting Goliath,

(b) Jacob wrestling the Angel,

(c) Daniel in the lions’ den,

(d) Jonah emerging from the mouth of the whale, and

(e) Samson slaying the lion.

Old Testament Scenes on 5 sides of the Pulpit

The scenes represent concepts of facing and enduring trials for which deliverance is eventually met. These themes connected with the Calvinistic theology of salvation through God’s grace alone without human intervention. The Puritans had adopted Calvinistic theology.

The base bracket of the pulpit is a convocation of eagles. At the top of the pulpit, on the corners of the frieze individual eagles stand on a platform above the capitals of a pair of arabesque decorated columns, and act as brackets to the top board.

The base frieze is of cartouches with strap work, with a form of caryatid depicting a well-endowed female top half and foliage bottom half. These imaginative and incongruous figures represent fertility symbolism. What is curious is that the one nearest to the altar rail on the south side has rather shiny breasts of a lighter colour than the rest of the pulpit. It appears that these have been touched or rubbed by hands over the years. Was it to do with prayer requests to God for children as they walked to the communion table? Or just an amusement?

Where did the decorative influence come from?

Wells, as a Cathedral city, would have had high-skilled joiners’ workshops. Anthony Wells-Cole’s work in his book, Art and Decoration in Elizabethan & Jacobean England: The Influence of Continental Prints, 1558-1625 (1997), has demonstrated that imported prints from the Netherlands transformed English decorative art in this period. He thinks it unlikely the joiners and carvers had direct access to the prints. The group that had the access were the wealthy patrons, who could supply them to the workshops of their choice.[v]

Cherub faces, geometrical shapes, and a scallop shell

Laudianism: Bishop William Piers, bishop of Bath and Wells

The Pulpit dates from 1636, when Laudianism was at its height. The period of 1632-1646 was when Bishop William Piers enforced the agenda of Archbishop William Laud across the Diocese of Bath and Wells. Laud was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633. The movement was a High-Church reform driven by Archbishop Laud and Charles I. It promoted a theological shift from the Calvinist predestination that had dominated the Church of England since Elizabeth I’s reign towards:

- the saving power of the sacraments (communion, in particular),

- an emphasis on free will, and

- the authority of bishops and clergy.

At a political level it supported the doctrine of the Divine Right of Kings and was established during the period of Personal Rule (1629 to 1640), the autocratic rule by Charles I without recourse to Parliament. The stance by Charles and the divisive religious policy, which set the puritan majority against the so-called ‘creeping Catholicism’ of the Anglican High-Church, led to the conflict of the First Civil War (1642 to 1646).[vi]

The Laudian reform translated into the physical church as “Beauty of Holiness”. This was the idea that the church space was to be one of dignity and visual splendour, connecting the physical with the spiritual. The impact was specific changes to parish church interiors, including:

- Communion Table – moved to the east end & set altar-wise

- Carved Rood Screens – separating the chancel from the nave

- Carved Pulpits

- Carved Communion Rails – where parishioners kneeled to receive communion

- Painted Ceilings

- Boxed Pews

- Stained Glass

- Ornamental Woodwork

The communion table caused conflict with the Puritans. During the Elizabethan settlement parish churches had a plain communion table set up at the centre of the nave or chancel. Communicants would gather in a sense of congregational worship. Laud ordered these tables to be moved to the east end of the chancel, to be railed in and furnished with plate and candlesticks. The table was to be placed altar-wise (i.e. north-south, rather than table-wise, orientated east-west).[vii] The vicar would stand with his back to the congregation and dispense the sacrament to kneeling parishioners. This felt too ‘catholic’ to the Puritans.

When the pulpit at St. Cuthbert’s was carved in 1636 it was the height of the crisis between the parish and Bishop William Piers, who was Bishop of Bath and Wells from 1632 to 1646. Then the events of the Civil War (1642 to 1651) included Parliament abolishing the English episcopacy in October 1646. The Restoration brought it back and Bishop Piers was restored in 1660 and remained in office until his death in 1670.

Before the abolition of the English episcopacy Bishop Piers went about his reforms. Some of the items were likely resisted or removed during the Civil War. In Somerset there were Puritan clothier districts, dominated by merchants and gentry of power and wealth such as at Frome and Beckington. Unfortunately, records are lacking from this period of history due to the disruption of the Civil War.

Bishop Piers was the first bishop to enforce the ruling from Canterbury that the altar be placed to the east wall and railed in. He moved to implement Charles I’s statement ‘parochiall churches should be like the cathedrall churche’.[viii]The Cathedral was to lead the liturgy of the Church of England.[ix] The bishops were to enforce the new conformity through church courts and visitations. Piers pushed through on reform. However, in 1636 there were only 140 churches of out 469 in the diocese that conformed. Some churches may have delayed awaiting the outcome from the Court of Arches (an ecclesiastical court of appeal for the Province of Canterbury) over the case of Beckington Church. The churchwardens, James Wheeler and John Fry, refused to obey Pier’s orders to move the communion table. Piers had them excommunicated and Archbishop Laud sentenced them to a year’s imprisonment and acts of public penance.[x]

Piers alienated many of the Somerset gentry. He clashed, for example, with Sir Francis Popham, patron of the parish of Buckland St. Mary, over the appointment of Popham’s son as incumbent upon a vacancy in 1636. In 1640 articles of accusation against Piers were presented to the House of Commons, which described him as a ‘desperately prophane, impious, turbulent Pilate’ (Articles of Accusation, 8). Archbishop Laud defended Piers, stating that he had done nothing but be obedient. Laud himself had been impeached in December 1640 and imprisoned. In December 1641, along with eleven other bishops, Piers was accused of high treason and committed to the Tower, after they had protested the legality of proceedings in the Commons during their enforced absence from the House of Lords. Piers was eventually released from the Tower.[xi] Archbishop Laud, however, was executed on 10 January 1645.

Piers appears to be zealous in his reforms, upsetting the Puritans and hunting down recusant Catholics.

A Pulpit Between Two Faiths?

In 1875 Thomas Serel, a leading member of the Wells and Glastonbury Antiquarian Society, described the 1636 pulpit at St. Cuthbert’s as being “a most incongruous character”.[xii] The pulpit is a complex design of grotesque work along with images of Biblical trials, nature fertility, framed within geometrical, arabesque, lion-face cartouches, strap work, Renaissance decoration, and incorporating eagles. A combination of serious themes of fortitude along with playful expression. The caryatid female forms are rather shocking for a church setting. It does not either comply fully with Puritan sensibilities or Laudian liturgical furnishings. It may well have been a way of St. Cuthbert’s expressing its independence and division from the dogmatic Bishop Piers at the nearby Cathedral. 1636 appears to be a year at the height of the division progressed by the reforming bishop. The pulpit is a fascinating expression of this time.

Of course, the story is never that clear. At Croscombe church near Shepton Mallet the Jacobean interior was installed circa 1616. This is before the Laudian era. Rood screens and altar rails were making appearances during the reign of James I.

SUMMARY

The pulpit has a feel of ordinary parishioners and craftsmen with the backing of wealthy patrons and the parish church officials, expressing their own feelings and uniqueness in this fascinating object. Bringing together ornamental fashion, Biblical fortitude and the whimsical, it forms an expression of independence from the Cathedral, finding a way to articulate in woodwork the style of the age in a community.

NOTES

[i] Susan Orlik, ‘The ‘Beauty of Holiness Revisited: An Analysis of Investment in Parish Church Interiors in Dorset, Somerset, and Wiltshire, 1560-1640’, PhD Thesis, 2018, University of Birmingham Research Archive, p. 152.

[ii] Thomas Scott Holmes, Wells and Glastonbury: A Historical and Topographical Account (London: Methuen & Co., 1908), p. 134.

[iii] Orlik, p. 152.

[iv] Orlik, p. 152.

[v] Orlik, p. 156.

[vi] Elizabeth Moore, ‘Worcester Cathedral and the Caroline Altar Policy: 1634-1642’, Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive Blog, 21 April, 2018 < https://worcestercathedrallibrary.wordpress.com/2018/04/21/worcester-cathedral-and-the-caroline-altar-policy-1634-1642/> [accessed 20 February 2026].

[vii] Moore, ‘Worcester Cathedral and the Caroline Altar Policy: 1634-1642’, Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive Blog.

[viii] M. Dorman, “Piers, William (bap. 1580, d. 1670), bishop of Bath and Wells.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 19 Feb. 2026. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-22237.

[ix] Moore, ‘Worcester Cathedral and the Caroline Altar Policy: 1634-1642’, Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive Blog.

[x] Dorman, “Piers, William (bap. 1580, d. 1670), bishop of Bath and Wells.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[xi] M. Dorman, “Piers, William (bap. 1580, d. 1670), bishop of Bath and Wells.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[xii] Orlik, p. 152.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Dorman, M. “Piers, William (bap. 1580, d. 1670), bishop of Bath and Wells.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 19 Feb. 2026. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-22237

Moore, Elizabeth, ‘Worcester Cathedral and the Caroline Altar Policy: 1634-1642’, Worcester Cathedral Library and Archive Blog, 21 April, 2018 < https://worcestercathedrallibrary.wordpress.com/2018/04/21/worcester-cathedral-and-the-caroline-altar-policy-1634-1642/> [accessed 20 February 2026]

Orlik, Susan Mary, ‘The ‘Beauty of Holiness Revisited: An Analysis of Investment in Parish Church Interiors in Dorset, Somerset, and Wiltshire, 1560-1640’, PhD Thesis, 2018, University of Birmingham Research Archive