Baptism is a key, and usually the initial, sacrament in the life of a Christian. Early Christians performed the rite with immersion in water. In the medieval Christian church, the process of infusion was practiced – the pouring of water on the head of the new member of the church.

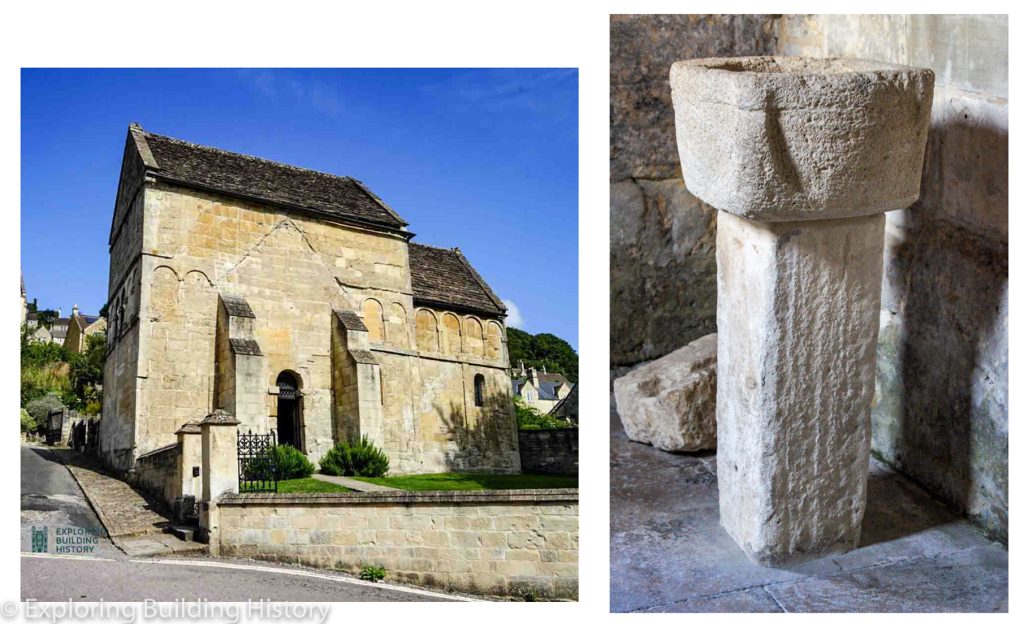

Anglo-Saxon Church of St. Laurence, Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire. Font: 10th C

The area of the church where the sacrament of baptism is performed is known as a baptistery. The original position of a church font is to the left of the south door. Often fonts can be found near the west door. Liturgically the position of the font needs to be close to the principal point of entry to a church. However, reordering in churches over the centuries has meant that the font may not be in its original position.[i]

The word ‘font’ comes from the Latin fons, meaning a natural spring.[ii]

Different font designs come from different times in the medieval period and can be helpful in dating the age of church. Although this needs to be approached cautiously as the font may have been moved from another source. Early fonts may have been sited directly on the ground. However, by the late-medieval period fonts were raised on a plinth, often with steps. The basin of the font would have been lined with lead with a drain hole through the stem and base into a soakaway. It is the soakaway that can inform church archaeology where the original position of a font was.[iii]

During the 13th C ecclesiastical law required that all fonts had lockable covers. In 1236, Edmund, archbishop of Canterbury, ordered that all baptismal fonts should be kept under lock and key as a precaution against sorcery.[iv] This meant there were iron straps and locks fitted. Some of the font covers became elaborate works of ornamentation. This continued through to the Reformation when many covers were forcibly removed. Sometimes evidence of this damage can be seen on font rims.[v]

Church of St. Candida & Holy Cross Font: Late-12th C

Notice on the rim – evidence of previous cover which has been removed

Years after the Reformation some churches added a font cover back again and these can be simple or elaborate. Also, font bowls were painted and occasionally evidence of this can be seen.[vi]

TUB FONTS

In the early-medieval period fonts were often tub-shaped, circular, or even square. Possibly the tub shape provided a means of immersion for a baby as a baptismal rite.

Church of St Basil, Toller Fratrum, Dorset. Mid-12th C Font with curious images.

Font St Basils Church, Toller Fratrum, Dorset

At the Cathedral Church of St. Andrew in Wells (Wells Cathedral) there is a font that dates from the original Anglo-Saxon cathedral (dates from 705 built by Aldhelm during the reign of King Ine of Wessex). However, it has been altered. It would have had figures and other decorative features on it originally. The current cathedral was started in 1175 and finished in 1306, and the font was moved into it. To fit in with the gothic cathedral the rounded arches of the font decoration were adjusted to include a point. The font cover dates from circa 1635.

Font at Wells Cathedral – Anglo-Saxon, altered to Norman and then Gothic (slightly pointed arches)

Wells Cathedral Font – notice slightly pointed arcade arches. Cover dates from circa 1635

NORMAN & EARLY ENGLISH

Font at the Church of St.Nicholas Corfe, Somerset. Font at the Church of St. Mary, Stocklinch Ottersey, Somerset. Font at the Church of St. Mary and St. Bartholomew, Cranborne, Dorset. Font at the Church of St. Michael Church, Winterbourne Steepleton, Dorset.

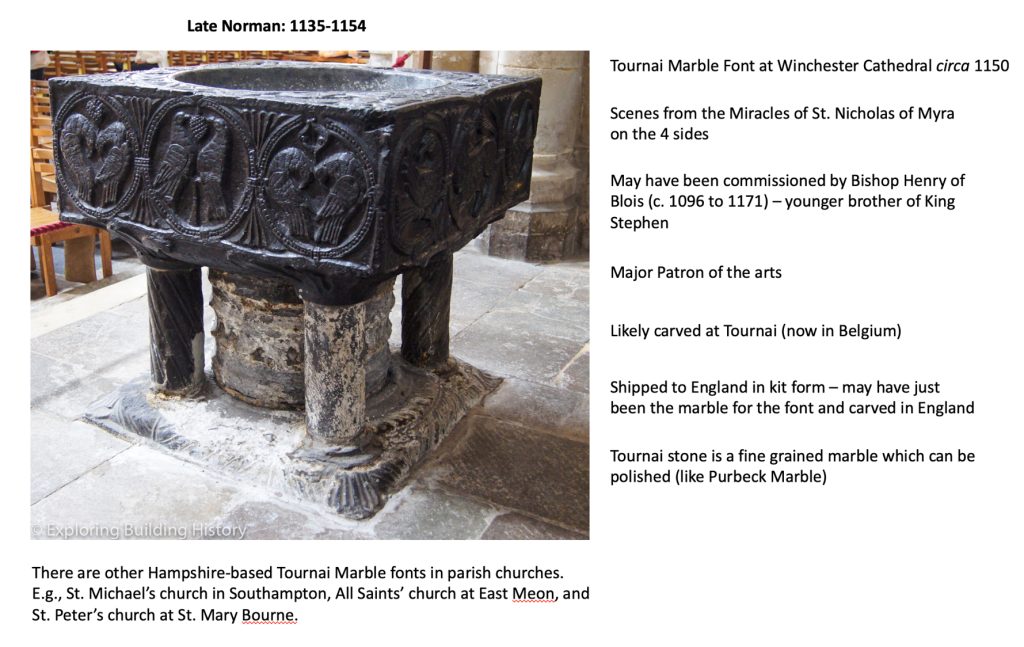

Square Tournai Marble Font at Winchester Cathedral. Late Norman: 1135 to 1154.

OCTAGONAL FONTS

From the 13th C octagonal fonts became increasingly common. The number 8 recalls the eighth day is the first day of resurrection. St. Augustine wrote about ‘the Day of the Lord, an everlasting eighth day.’ St. Ambrose explained that ‘on the eighth day, by rising, Christ loosens the bondage of death and receives the dead from their graves.’[vii] The number eight also relates to the concept of a new creation and links the circumcision of Christ on the eighth day after his birth.

The octagonal baptistery model was a common shape from early Christian times. The Lateran Baptistery in Rome, dating from 440 AD, provided the model for later baptisteries. One of the most famous is the beautiful Baptistery of St. John in Florence (1059-1128). The octagonal font of the English parish church follows this tradition on a much smaller scale starting in the 13th C.

Early & Late Decorated Fonts: Font at the Church of St. John the Baptist at Bere Regis, Dorset. Font at the Church of St. Michael, North Cadbury, Somerset. Font at the Church of All Saints, Castle Cary, Somerset.

Early Perpendicular Font at the Church of St. Michael, Minehead, Somerset.

Late Perpendicular Fonts. Font at the Church of St. Mary, Stogumber, Somerset. Font at the Church of St. Martin of Tours, Lillington, Dorset. Font at the Church of St. Thomas of Canterbury, Cothelstone, Somerset.

The octagonal font became the norm of the Perpendicular period of the 14th century onwards. Many have a standard design with ornamentation of tracery, shields, coats of arms, and other heraldic devices. It suggests that there were specialist workshops producing standard fonts.

SEVEN SACRAMENT FONT: Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Nettlecombe, Somerset

However, there are those that are ornamented uniquely or with the seven sacraments (the eighth panel used for another scene such as Christ in Majesty).

The Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Nettlecombe, Somerset. Seven Sacraments Font, Later Perpendicular.

Detail of the Sacraments of Holy Orders, Marriage, and Extreme Unction (Anointing the Sick)

Detail of the Sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, Penance, and the Eucharist

Between 1886 and 1907 Harvey Pridham surveyed and made drawings of many of Somerset medieval fonts. He wrote in 1899 about Somerset fonts:

‘The fonts of Somerset, speaking as a general rule, may be said to be a medium between two extremes. They have not the curious, and, in many cases, remarkable wealth in the Grotesque which characterises the Cornish work, nor are they converted into sculpture galleries like those of East Anglia… The fonts of Somerset, while not able to claim superiority over either extreme, are more severely architectural than either, though not so curious as one, nor so magnificent as the other. Without making further comparisons with our neighbours, we may claim to have a wonderful variety in design, although a very large number are severely plain. As might be expected in a county so identified with Perpendicular style, there is an approach to monotony in a few of the fonts of that date.’[viii]

ENGLISH RENAISSANCE FONT – Post Reformation

The font at the Church of St. James, Swimbridge, near Barnstaple in Devon, is a unique and elaborate one. It is essentially a lead-lined hexagonal font in a highly ornamented cupboard. The doors can be closed or folded back to reveal the font. The carving is of the English Renaissance period of the 16th century. Probably late Elizabethan and has kept to non-religious imagery. There are putti faces with wings. There are roundels or medallions with faces in profile. Possibly these portraits in profile are of the patron family that paid for the font. Ruling and wealthy families of the Italian Renaissance had popularised portrait medals as a status object which was used as a prestigious diplomatic or courtly gift to others. Revived from the classical practice of putting emperors’ busts on roundels, medallions, and coins. Leon Battista Alberti (1406-1472) had been the first artist to make a self-portrait medallion. The practice had found its way onto woodwork in Swimbridge in north-west Devon by the late 16th C.

English Renaissance Carved Font at the Church of St. James, Swimbridge, near Barnstaple, Devon

The canopy may have come from a pulpit as it is somewhat incongruous but may have been part of the original design

Detail of roundels or medallions with portraits in profile. Renaissance details of leaves and putti.

Notes on the Rite of Baptism in the Medieval Period

The following are notes I have made from Nicholas Orme’s excellent book Going to Church in Medieval England. Well worth a read.

The first known baptism in England was that of Eanfled, the baby daughter of King Edwin of Northumbria in 625. The practice of the early Christian Church was to concentrate baptisms at Easter Eve or Pentecost Eve. However, anxieties about the salvation of the unbaptised if they died before the baptism pushed for infants to be baptised soon after birth. The two approaches caused tension in the Anglo-Saxon period. A law attributed to King Ine of Wessex (d. 726) stated that an infant be baptised within thirty days of birth. A Church synod of 786 required that baptism must not occur outside of Easter and Pentecost unless absolutely necessary.[ix] A Church council at Winchester of 1070 reiterated this requirement.[x]

By the 12th C immediate baptism became the norm – usually on the day the child was born. This required the godparents to be on hand and was also a ceremony of naming. Godparents were part of the rite since Anglo-Saxon times. In the 12th C the requirement was to have three godparents – two of the infant’s own sex, and one of the other. Often the principal godparent’s name was given to the child. Families could end up with children with the same name due to this custom. A higher-status godparent may provide advantages of patronage in the child’s life. However, it also meant from the Church’s perspective that the godchild could not marry into their godparents’ family.[xi]

The danger of infant mortality meant that the Church could depute the rite to a lay person in emergencies. Ideally this should be a man, but midwives were on hand often and could perform the words and sprinkle the water. The parish clergy could interrogate afterwards to ensure the correct words and procedure was followed.[xii]

A Church baptism began at the church door. Like the services for marriage and churching (the formal return of a mother after giving birth – a period of usually forty days absence[xiii]), it is rite of transition from outside the church to the inside. The building of church porches in the later medieval period helped those sheltering before entering for such rites. The infant was brought by the midwife and accompanied by family members and godparents. The mother would be resting at home.[xiv]

From the 13th C consecrated water was kept in the font in preparation for emergency baptisms. The water was renewed every week. Although the nobility, gentry, and wealthy wanted fresh water for the baptism of their infants and the priest performed a more elaborate consecration of the water as part of the ceremony.[xv]

Besides water the infant would be anointed with chrism in the shape of a cross on the crown of the head. The infant would then be wrapped in a white cloth, known as the ‘chrisom cloth’. It became holy at this point as it had come into contact with the consecrated chrism oil. The cloth would be returned to the church for use in future baptisms.[xvi] The chrism cloth was usually given back at the churching service by the mother upon her return after having given birth.[xvii]

Standardisation of Liturgical Rites: The Use of Sarum & The Use of York

Parish churches followed the liturgical rites of those laid down by the cathedral within whose province it resided. These provinces were the two archbishoprics of England – York and Canterbury. York was a secular cathedral and the rite transferred easily onto the parish churches of the north of England (the ‘Use of York’). However, Canterbury was a monastery, and it was not straightforward for parishes to take up the monastic services. The consequence was that the secular cathedral of the south of England became the models for parish worship. These were Exeter, Hereford, Chichester, Lichfield, Lincoln, St Paul’s in London, and Salisbury. It was from Salisbury that the standardisation came in the 13th and 14th centuries – the ‘Use of Sarum’ or the ‘Sarum Rite’. This became the model for the parish churches in the diocese of Canterbury apart from Hereford where its own customs prevailed locally.[xviii]

NOTES

[i] Warwick Rodwell, The Archaeology of Churches (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2012), p. 161.

[ii] Geoffrey R. Sharpe, Historic English Churches: A Guide to their Construction Design and Features (London: I. B. Tauris & Co., 2011), p. 225.

[iii] Rodwell, p. 161.

[iv] Robert Alexander Steward Macalister, ‘Font’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 10, 1911 < https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclopædia_Britannica/Font> [accessed 28 May 2022].

[v] Rodwell, p. 162.

[vi] Rodwell, p. 162.

[vii] ‘Theological Reasons for Baptistry Shapes’, Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/theological-reasons-for-baptistry-shapes/ [accessed 29 May 2022].

[viii] Ancient Church Fonts of Somerset: Surveyed & Drawn by Harvey Pridham, ed. Adrian J. Webb (Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, 2013), pp. 3-4.

[ix] Nicholas Orme, Going to Church in Medieval England (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021), pp. 10-11.

[x] Orme, p. 302.

[xi] Orme, pp. 302-4.

[xii] Orme, p. 304.

[xiii] Orme, p. 314.

[xiv] Orme. pp. 304-7.

[xv] Orme, pp. 308-9.

[xvi] Orme, pp. 310-11.

[xvii] Orme, p. 314.

[xviii] Orme. pp. 200-11.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ancient Church Fonts of Somerset: Surveyed & Drawn by Harvey Pridham, ed. Adrian J. Webb (Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society, 2013)

Macalister, Robert Alexander Steward, ‘Font’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume 10, 1911 < https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclopædia_Britannica/Font> [accessed 28 May 2022]

Orme, Nicholas, Going to Church in Medieval England (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021)

Rodwell, Warwick, The Archaeology of Churches (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2012)

Geoffrey R. Sharpe, Historic English Churches: A Guide to their Construction Design and Features (London: I. B. Tauris & Co., 2011)

‘Theological Reasons for Baptistry Shapes’, Calvin Institute of Christian Worship, https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/theological-reasons-for-baptistry-shapes/ [accessed 29 May 2022]