Chantries of Bishop Richard Fox & Bishop Stephen Gardiner

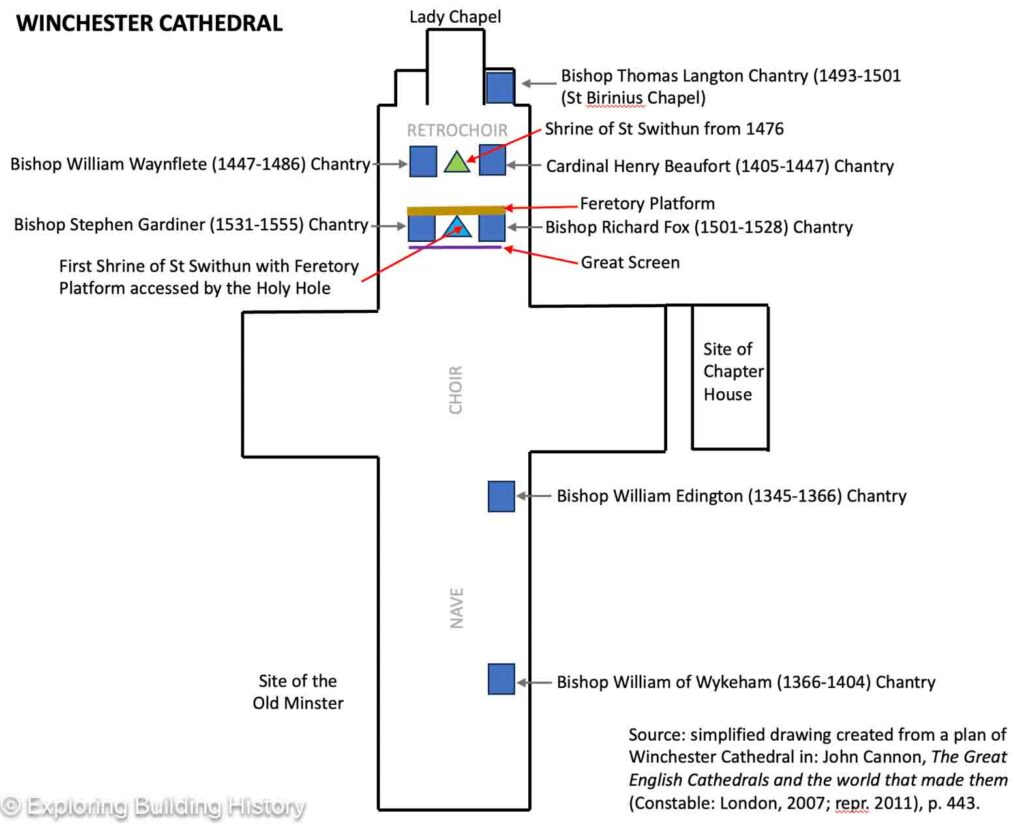

Flanking the old shrine of St Swithin and the feretory platform at Winchester are two chantries belonging to the first half of the 16th Century. One displays the height of mastery of the late Perpendicular Gothic and the other moves on into the Renaissance with striking examples of both early and high Renaissance expression.

| Years as Bishop | Location of Chantry | ||

| 1 | Richard Fox | 1501-1528 | S side of original position of St Swithin Shrine |

| 2 | Stephen Gardiner | 1531-1555 | N side of original position of St Swithin Shrine |

Bishop Richard Fox (Bishop from 1501 to 1528)

Richard Fox was a member of Henry VII’s cause. He was present on the 22nd of August 1485 at Bosworth field when Richard III was defeated. He was Secretary and Keeper of the Seal to both Henry VII and Henry VIII and dedicated to service of the monarch.[i] He was active in architectural projects, which included[ii]:

- Fortification Strenthening: Calais and Norham Castle, Northumberland

- Durham Castle: improved the hall and built the new kitchen

- Royal Works: Likely involved in building work at Westminster & elsewhere. He took some responsibility for planning the glass at King’s College Chapel, Cambridge

- Winchester: completed the reconstruction of Waynflete’s east end work; the great east gable, the high vault, aisle and presbytery screen. The presbytery screen involved the creation of cornices formed to support the bones of Anglo-Saxon kings, queens, and bishops in mortuary chests, known as ‘Fox’s Boxes’.[iii]

Mortuary Chests on Chancel Screen. The chest containing King Canute & Queen Emma & King Harthacnut is the one on the right nearest to the Bishop’s throne

Bishop Fox redesigned the east end with a high vault ceiling, decorated with shield bosses that represented his episcopal career: Exeter, Bath & Wells, Durham and Winchester.[iv]

He founded Corpus Christi College, Oxford. The foundation was on the 1st of March 1517 for a president, twenty fellows and twenty scholars. Public readers were provided in ‘humanity’ and Greek. The aim was the training of priests by means of literature and theology. The emphasis was on moral formation and represented the most complete example of a humanist college.[v]

It is likely he was involved in the foundation of Christ’s College, Cambridge in 1505 and St John’s College, Cambridge in 1511. He was elected chancellor of Cambridge in 1498-9 and master of Pembroke College, Cambridge from 1507 to (probably) 1516.[vi]

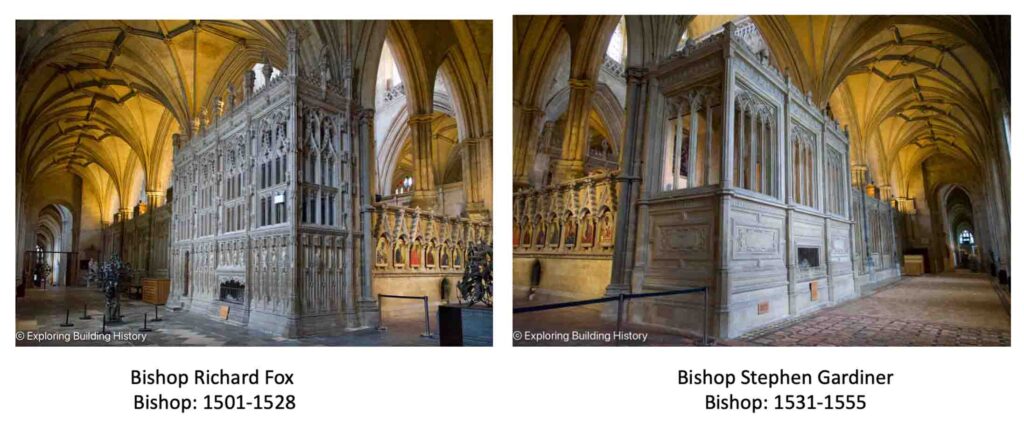

He took a great interest in his own chantry, having it built in his own lifetime. It is known as ‘Fox’s Study’. This comes from the latter days of Fox’s life when he was blind and spent many hours seated in his chantry in prayer and meditation.[vii]

The chantry was ‘newly built’ by 1518[viii], ten years before Fox’s death. The King’s Master Mason from 1510 was William Vertue, and he likely designed Fox’s chantry. Humphrey Coke, the master carpenter who worked with Vertue on the design of Corpus Christi College, Oxford (from 1512) likely worked on it too.[ix] The design does have a carpenter’s flair, with stone articulated like woodwork.

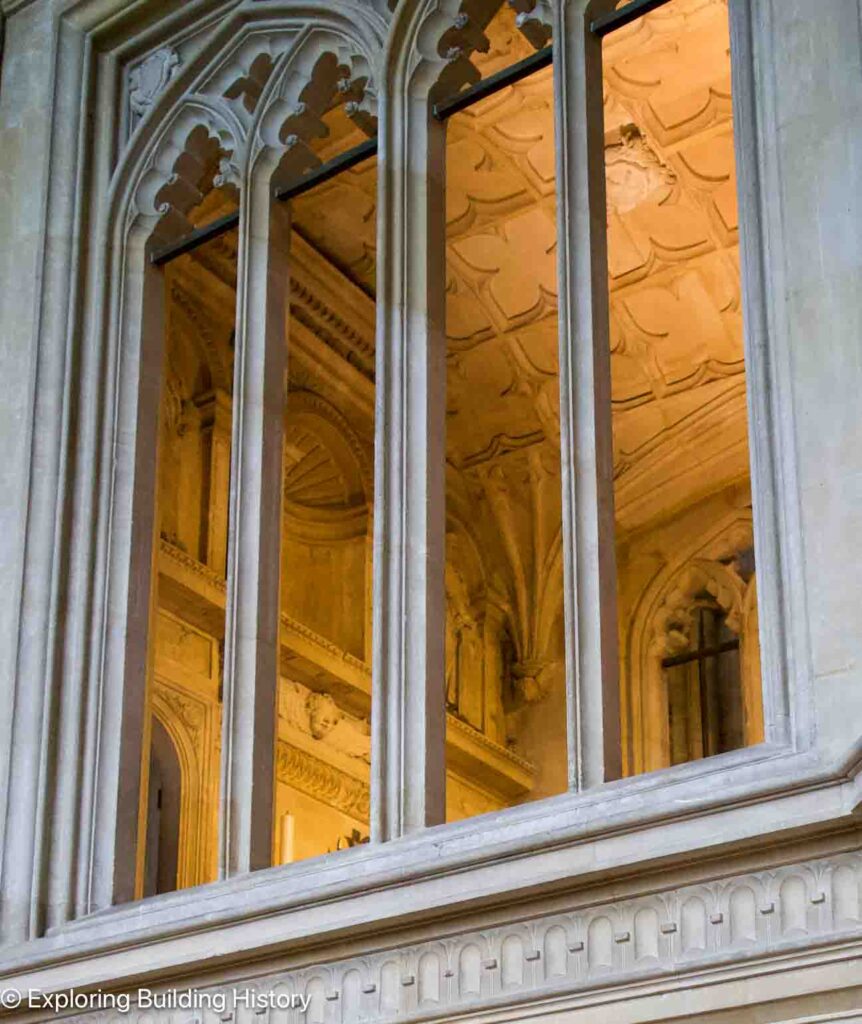

Chantry of Bishop Richard Fox: A last great flourish of Perpendicular Gothic architecture. This wonderful, regular, finely ornate chantry was probably designed by the royal mason, William Verne with master carpenter, Humphrey Coke.

The panels of bar tracery are delicately elaborated to include ogee arches, with spandrels and crockets. There are small niches for statues. The stone carving is a masterpiece.

The ‘memento mori’ cadaver effigy of the bishop is to remind the viewer that life is transient.

The stone carving is reminiscent of wood carving it is so delicate and intricate.

Pelicans are a striking feature of the chantry. The Christian symbolism refers to the sacrificial concept of the pelican pecking at her own chest to feed her young.

Statues are modern replacements. The original ones were destroyed in the Reformation.

Foxe’s predecessor, Bishop Thomas Langton’s chantry chapel, demonstrates the mastery of carpentry in Perpendicular ornament. Bishop Foxe’s chantry responds in kind with mastery in stone.

Bishop Thomas Langton’s Chantry Chapel (bishop from 1493 to 1501)

Bishop Stephen Gardiner (Bishop from 1531 to 1555)

When Bishop Fox died his successor was briefly Cardinal Wolsey (bishop from 1529-30). Then Bishop Stephen Gardiner was consecrated in 1531. He would witness the Dissolution in full force at Winchester in 1528. In September 1528 Henry VIII’s officials ‘made an end’ of the shrine St Swithun, recovering some 2000 marks of silver and fake jewels. St AEthelwold’s (Bishop of Winchester from 963 to 983) monastic reform in the latter part of the 10th century had ejected the secular canons from the Old Minster and replaced them with monks. Now it was back to secular canons.[x]

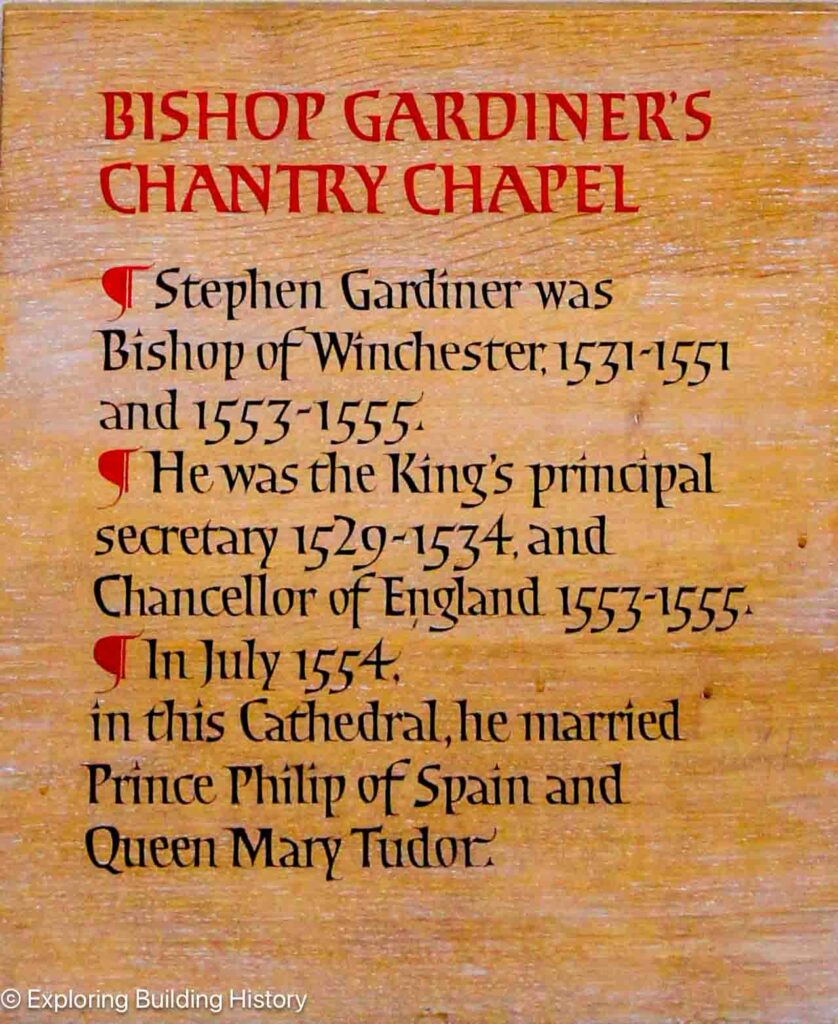

Erasmus (c. 1466 to 1536), a Christian humanist was a key influence on the Northern Renaissance. Bishop Fox had met him, as did Stephen Gardiner. Although Gardiner met Erasmus in Paris when he was still a boy. Gardiner’s patron was Cardinal Wolsey. He also came to the notice of Henry VIII and in 1529 became his principal secretary. Gardiner was a key player in the attempt of Henry VIII to gain a divorce from Katherine of Aragon. Although it was not that fortuitous for him and Gardiner became less trusted by Henry and replaced by Thomas Cromwell as royal secretary. He would get back to court after Cromwell’s fall.[xi]

Gardiner became Wolsey’s successor to the see of Winchester in September 1531. He was imprisoned during Edward VI’s reign but his star rose again under Mary I’s accession and he was appointed lord chancellor in 1553. He presided over the marriage of Mary I & Philip II of Spain at Winchester Cathedral on the 25th of July 1554.[xii]

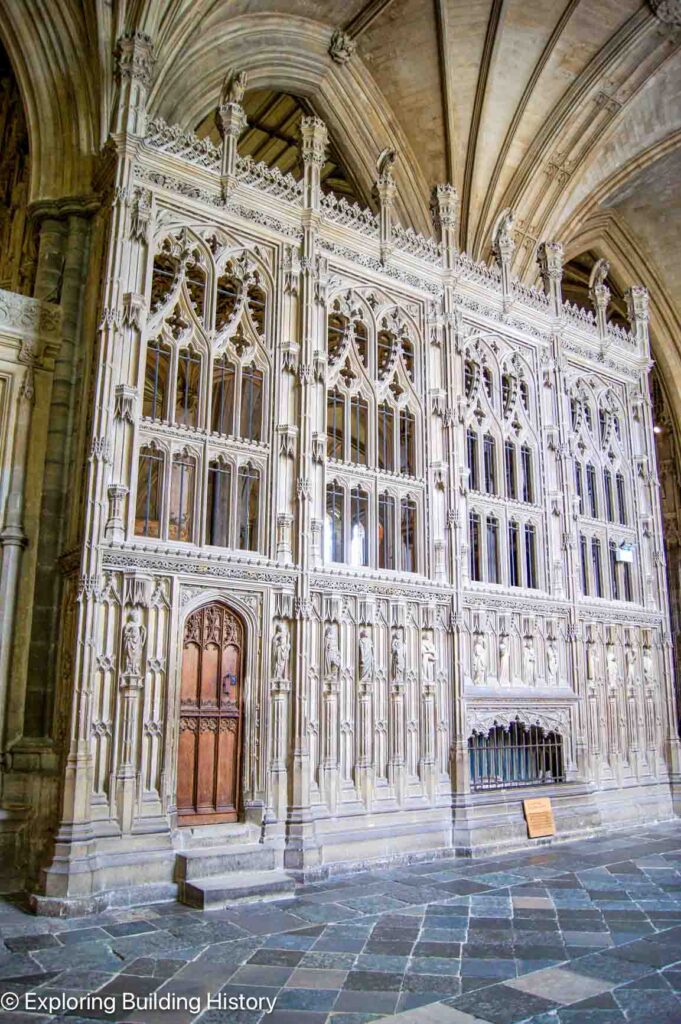

His chantry in a curious mixture of Gothic with early and high Renaissance elements. The Pevsner guide for Hampshire: Winchester and The North describes it as: ‘far from homogenous. It is Gothic in parts, Early Renaissance in parts and as early as anywhere in England High Renaissance in parts’.[xiii]

A summary of the description of the chantry in the Pevsner guide is as follows:[xiv]

- 3-bay structure

- Elevated substructure containing the burial chamber

- Martin Biddle stated that the High Renaissance is in the Mannerist style, derived from Henry VIII’s Nonsuch Palace

- Scroll work cartouches in rectangular frames on substructure

- High Renaissance entablature with triglyph frieze and metopes alternating with bucrania and paterae.

- Above the Cinquecento frieze is a balustrade or parapet of Early Renaissance style – strapwork, grotesque masks and the bishop’s arms

- At the east end interior there is a panel for a reredos behind the altar, with double guilloche frame.

- Central shell headed niche; either side are Ionic colonettes – amongst the earliest examples in England

Ionic colonettes can just be seen. A type of quatrefoil coffered ceiling (a mixture of Renaissance and Gothic). The parapet or balustrade is a complex mixture of ornament.

A Serlian-inspired shell-headed niche. On the frieze below a cherub can be seen.

The ‘momento mori’ of Bishop Gardiner

Bishop Stephen Gardiner was the last Roman Catholic bishop of Winchester. The Dissolution of the Chantries 1547 under Edward VI had stripped the existing chantries of funding, priests and valuables. This was a last, late flourish of the ‘chantry’, although not technically one as they were still illegal but still geared up for a priest.

Edward VI (r. 1547-1553) had deprived Gardiner of his see and Mary I (r. 1553-1558) restored him to his bishopric. Mary I married Philip of Spain (later Philip II of Spain) on 25 July 1554 at Winchester Cathedral with Bishop Gardiner presiding. He died a year later in 1555 at the age of seventy-two. The chantry would have been built at the time of Mary’s reign as it would not have been allowed under Elizabeth I.

NOTES ON THE RENAISSANCE AT WINCHESTER

These chantries straddle the Gothic and the Renaissance eras. Jon Cannon mentions that in the chantry chapel of Bishop Thomas Langton (d. 1501) are some of the earliest, hesitant Renaissance details in England. Langton had travelled to Padua, Rome and Bologna.[xv] I will have to investigate next time I am at Winchester.

Cardinal Beaufort (d. 1447) had travelled to Venice, an early Renaissance centre, and had his portrait painted by the Northern Renaissance artist Jan van Eyck. Beaufort’s portraits is one of the earliest portraits in England.[xvi] The concept of Humanism developed in key centres, such as Florence, and portraiture was part of a new exploration of emphasising man and reason. Architecture was developing into classical motifs expressed in symmetry, order of columns, friezes, entablatures, niches and domes. This was replacing the soaring upwards of the crocketed pinnacles, ogee arches, tracery with quatrefoil and cinquefoil arch headers, fan vaulting with bosses of the High Perpendicular Gothic. Although, symmetry was always pleasing in this architectural period too!

New ideas were forming at Winchester. Bishop Fox had founded Corpus Christi at Oxford, initially for monks, but realised society was changing and made it a secular college.[xvii] It would be the first place in England to teach Ancient Greek[xviii], which formed part of a new curriculum favoured by humanists. Interest in ancient texts was revived by the Renaissance with the rediscovery of classical works in monastic libraries and the flow west of works by Arabic scholars, who had secured many classical originals after the Fall of Rome.

‘Fox’s Boxes’, with the bones of the Anglo-Saxon kings and queens, which sit atop Bishop Fox’s presbytery screen are Italianate in their design.

King Cnut, Queen Emma & King Harthacnut

King Edred (d. 955)

SUMMARY

The bishops at Winchester with their cage chantries were not the quiet, retiring sort. They were magnates of England with power, influence and wealth. They ensured they were at the forefront of ideas, making a reality in stone of their time. The latest Gothic designs, followed by the emergence of the Renaissance were pushing at the open door of Winchester. With access to royal masons, some of the finest work in the country lies in this great cathedral.

NOTES

[i] C. S. L. Davies, “Fox [Foxe], Richard (1447/8–1528), administrator, bishop of Winchester, and founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-10051 [accessed 23 September 2025].

[ii] C. S. L. Davies, “Fox [Foxe], Richard (1447/8–1528), administrator, bishop of Winchester, and founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[iii] Jon Cannon, The Great English Cathedrals and the world that made them (Constable: London, 2007; repr. 2011), p. 450.

[iv] Cannon, p. 450.

[v] C. S. L. Davies, “Fox [Foxe], Richard (1447/8–1528), administrator, bishop of Winchester, and founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[vi] C. S. L. Davies, “Fox [Foxe], Richard (1447/8–1528), administrator, bishop of Winchester, and founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[vii] John Crook, Winchester Cathedral (Andover: Pitkin, 1990; repr. 1996), p. 16.

[viii] Michael Bullen, John Crook, Rodney Hubbuck & Nikolaus Pevsner, Hampshire: Winchester and The North, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), p. 599.

[ix] Michael Bullen, John Crook, Rodney Hubbuck & Nikolaus Pevsner, p. 599.

[x] Cannon, p. 450.

[xi] C. Armstrong, (2008, January 03). Gardiner, Stephen (c. 1495×8–1555), theologian, administrator, and bishop of Winchester. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-10364 [accessed 25 September 2025].

[xii] C. Armstrong, (2008, January 03). Gardiner, Stephen (c. 1495×8–1555), theologian, administrator, and bishop of Winchester. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[xiii] Michael Bullen, John Crook, Rodney Hubbuck & Nikolaus Pevsner, p. 597.

[xiv] Michael Bullen, John Crook, Rodney Hubbuck & Nikolaus Pevsner, pp. 597-8.

[xv] Cannon, p. 449.

[xvi] Cannon, p. 448.

[xvii] Cannon, p. 449.

[xviii] Cannon, p. 449.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Armstrong, C., (2008, January 03). Gardiner, Stephen (c. 1495×8–1555), theologian, administrator, and bishop of Winchester. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-10364[accessed 25 September 2025]

Bullen, Michael, Crook, John, Hubbuck, Rodney, & Pevsner Nikolaus, Hampshire: Winchester and The North, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010),

Cannon, Jon, The Great English Cathedrals and the world that made them (Constable: London, 2007; repr. 2011)

Crook, John, Winchester Cathedral (Andover: Pitkin, 1990; repr. 1996)

Davies, C. S. L., “Fox [Foxe], Richard (1447/8–1528), administrator, bishop of Winchester, and founder of Corpus Christi College, Oxford.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-10051[accessed 23 September 2025]