From the 16th century the expression of neo-classicism is beloved by gentry. They wish to demonstrate their education and taste in elaborate ways. Tomb monuments are a fixed mechanism of doing this. Neo-classical taste is a trying to hark back to beyond the Gothic, Romanesque, and Anglo-Saxon to a perceived ideal of a classical world. In Italy from the 14th C classical texts were sought out, such as in monastic libraries, to inform a growing interest in statecraft, education, science, culture, art, and architecture. This movement birthed the Renaissance which flourished in a great wave of innovation in culture, learning, and thought across Italy and Northern Europe. The wave eventually travelled across to England and the new culture formed into something uniquely English.

Northern European artisans fleeing religious conflict did come to England. The native artisans and craftsmen had to adapt away from their honed Gothic skills into a new form of expression and ornament.

The micro architecture of the tomb of Sir John Pole and his wife Elizabeth at the Church of St. Andrew in Colyton is a good example of the English Renaissance in all its curious eclecticism.

Tomb Monument of Sir John Pole (d. 1658) and his wife Elizabeth (d. 1628).

Sir John Pole, 1st Baronet was the eldest surviving son of the antiquarian Sir William Pole (1561-1635) and Mary Peryam (1567-1605). Sir William and Mary had 6 sons and 6 daughters together.

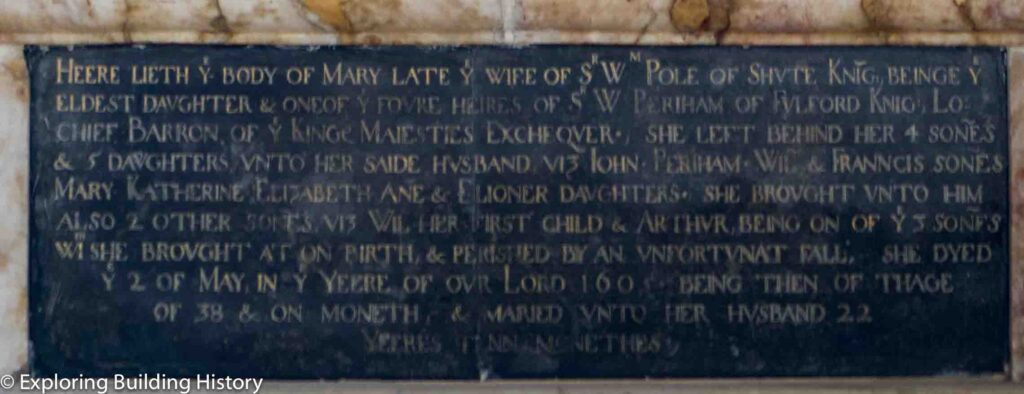

Monument of Sir William Pole’s wife, Mary (d. 1605)

Written on Mary’s monument in the Pole chapel it is stated she had triplet sons, and that Arthur, one of the 3 sons, died after an unfortunate fall. See my transcript:

Heere lieth the body of Mary late the wife of Sr Wm Pole of Shute Knig, beinge the eldest daughter & one of the foure heires of Sr W Periham of Fulford Knig Lo Chief Barron of the Kinge Majesties Exchequer. She left behind her 4 sones & 5 daughters unto her saide husband viz John Periham Wil & Francis sones Mary Katherine Elizabeth Ane & Elinor daughters. She brought onto him also 2 other sons viz Wil her first child & Arthur being on of the 3 sons which she brought at on(e) birth & perished by an unfortunat fall. She dyed the 2 of May in the yeere of our Lord 1605 being then of the age of 38 & on(e) moneth & maried unto her husband 22 yeeres …

Inscription on Mary Pole’s monument

It is not clear where the tomb for Sir William Pole is. Historic England states that Sir William Pole lies in the Pole Chapel without a memorial.[i] It is rather curious that Sir William ensured memorials for his wife and parents, but no such prominent tomb exists for him. His son, Sir John, by complete contrast has a very elaborate tomb.

The elaborate monument of Sir John and his wife possesses that element of not just being a memorial but a conversation piece. It is built like a mini temple with 2 structures of red-marble effect Corinthian columns, with gilded capitals holding up a triumphal arch. There is much elaboration of coloured ribbon scrolls, armorial shields, allegorical figures, putti, epitaphs in strap work.

Elizabeth, Sir John’s wife, died in 1628 and her epitaph is in Latin. Sir John’s dates are c. 1589 -1658 and his epitaph is in English. They lie back-to-back. He faces towards his ancestors in the Pole chapel, she faces away and into the chancel. They both lie awkwardly, resting on their sides, sharing the same cushion for support.

Elizabeth is dressed in black with ruffled cuffs and a falling band collar. The lacy scallop design of the collar drapes softly over her shoulders and onto the cushion she rests on. Under her left hand is a skull, a symbolic memento mori, reminding the viewer of the inevitability of death whatever your station in life.

Sir John is in his half armour and curiously has a ruff collar, which at his death in 1658 would have been well out of date. The ruff is large, which was the fashion in late-Elizabethan England, when starch was used to enable the increase in width. In his left hand he is holding a book. He wears his boots and sword and has a fine moustache and small beard, similar to the fashion of Charles I.

Bronze of Charles I at Kingston Lacy House, Dorset.

Charles was executed in 1649. From 1649 until 1660 England was ruled as a Commonwealth. Sir John lived through a turbulent period of history that included the execution of a monarch, the Civil War, and the Commonwealth.

Sir John would have been around 60 years of age at the time of Charles I’s execution. He died around the age of 69 and did not witness the restoration of the monarch, Charles II. When his wife died, he would have been around 39 years of age. The monument image is that of a man at the height of his vigour and status.

At the top end there is an image of a child’s head, perhaps a predeceased child.

The hourglass is another memento mori symbol. One of the putti holds an hourglass on top of the tomb.

At the Church of St. Andrew, Curry Rival in Somerset, is the Jennings tomb dating from circa 1630. The canopy over the tomb has wingless putti balancing an hourglass on their knee in a different pose to Sir John’s monument. But a similar motif.

On a nearby wall to Sir John’s monument, the hourglass and skull memento mori are a key theme on the Drake memorial from the early 17th C. This wall monument neatly includes classical devices, colour, and pious figures, capturing that unique flair of the English Renaissance.

Drake Wall Monument at Colyton Church – the date of 1617 is on the top of the monument.

Drake Wall Monument – Wingless putti with hourglasses on their knee like the Jennings monument. They appear to also be holding smart phones but I think they are books!!

SHAKESPEARE CONNECTION: Nicholas Johnson of Southwark?

In the Historic England entry for St. Andrew’s church at Colyton, it is stated that the monument of Sir John Pole and his wife was possibly sculpted by Gerard Johnson of Southwark.[ii] However, if it came from the Johnson workshop, it may have been his brother, Nicholas that made it.

The Johnson family were a workshop of sculptors operating in Southwark, close to the Globe Theatre. Gheerat Janssen (Gerard Johnson the elder) moved to London from the Netherlands, possibly as a protestant refugee. Two of his sons, Gerard the younger (fl. c. 1612) and Nicholas (d. 1624) worked alongside their father. The family appear to have been operating from c. 1570 to c. 1630. The only certain record for Gerard the younger is a payment for making part of a fountain for the east garden at Hatfield House.[iii]

William Dugdale recorded in his diary for 1653 that Shakespeare’s monument at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford upon Avon, was by ‘one Gerard Johnson’. This likely refers to the son and not the father, although the younger Gerard’s date of death is not known.[iv] But was it Gerard the younger that made the monument?

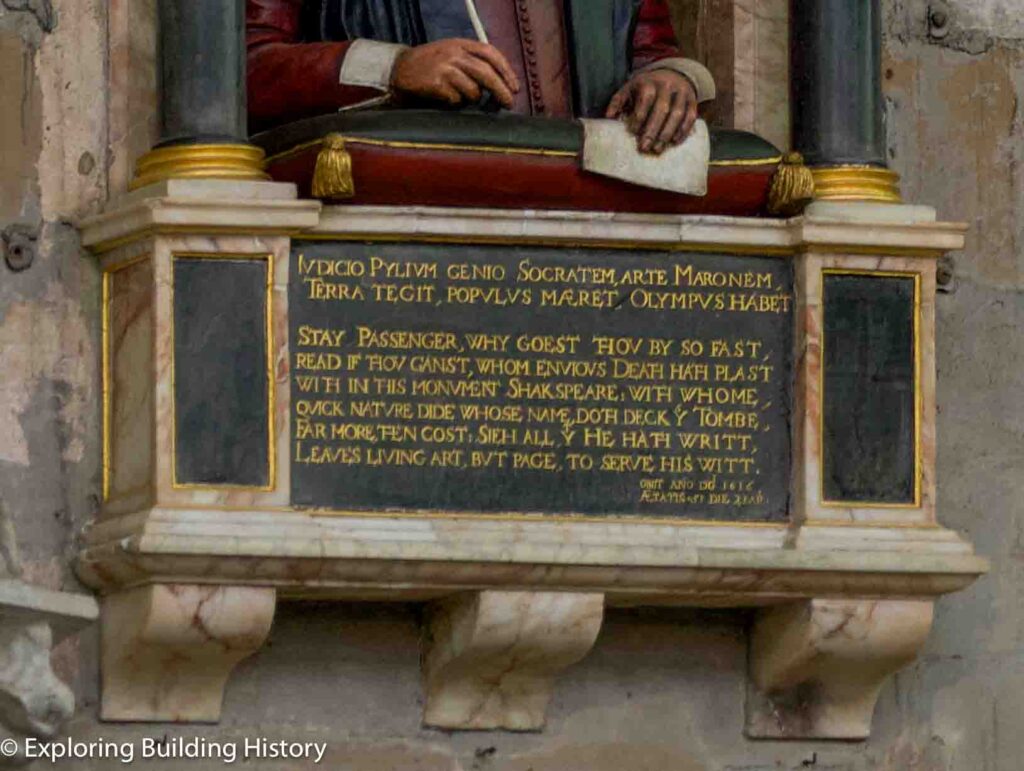

Shakespeare’s monument at Holy Trinity Church, Stratford upon Avon.

In The Guardian in 2021, Professor Lena Cowen Orlin (Professor of English at Georgetown University in the US) is quoted as having said: “It is highly likely that Shakespeare commissioned the monument. It was done by someone who knew him and had seen him in life. We can think of it as a kind of life portrait, a design for death that gives evidence of a life of learning and literature.”[v] She argues that it was not Gerard Johnson that sculpted the limestone monument but his brother Nicholas. Gerard had been identified as working on the fountain at Hatfield House, but Nicholas was the tomb-maker. She also argues that the memorial was created in Shakespeare’s lifetime as space was left on the plaque to add the inscription after his death.[vi]

Inscription on Shakespeare’s monument

So, could Nicholas Gerard, the tomb-maker, have designed and built the monument of Sir John Pole and his wife, Elizabeth?

Skull mask and putti on top of Shakespeare’s monument

SUMMARY

The tomb monument of Sir John Pole and his wife, Elizabeth is striking and theatrical. The red marble effect columns with gilded capitals remind me of the ones on the stage of the reconstructed Globe theatre in London. With the connection to the Johnsons of Southwark was there may have been a connection to theatre design.

I find myself puzzling over Sir John Pole’s ruff being so out of fashion by the time he died in 1658, although the effigy is that of a much younger Sir John. I wonder if the effigy and monument were created at the time of his wife’s (Elizabeth) death in 1628. The larger, starched ruff did continue into the early part of the 17th C but was generally out of fashion by the time Charles I came to the throne in 1625.[vii] Although Sir John does have the longer hair, moustache and beard that was fashionable at the time of Charles I. The Latin inscriptions could have been inscribed at the time of Elizabeth’s death in 1628, and the English version for Sir John added to the tomb in situ at the time of his death in 1658.

Sir John’s father, Sir William Pole died after Elizabeth in 1635 and lies without a tomb monument, the complete contrast to his eldest son. Sir William is likely to have seen the tomb monument of his son. Maybe he wanted the opposite!

In terms of the tomb maker(s), it maybe that the structure was made in the Johnsons’ workshop, possibly by Nicholas and others and transported down to Devon. Does the Jennings tomb at St. Andrew’s at Curry Rival, Somerset come from the same workshop, I wonder?

NOTES

[i] ‘Church of St Andrew’, Historic England List Entry 1306035, (1967), https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1306053?section=official-list-entry [accessed 5 November 2023].

[ii] ‘Church of St Andrew’, Historic England List Entry 1306035, (1967).

[iii] Adam White, ‘Johnson [formerly Janssen] family (per. c. 1570- c. 1630’), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004: online edn, Sept 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/73268 [accessed 5 November 2023].

[iv] White, ‘Johnson [formerly Janssen] family (per. c. 1570- c. 1630’).

[v] ‘‘Self-satisfied pork butcher’: Shakespeare grave effigy believed to be definitive likeness’, The Guardian, 19 Mar 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2021/mar/19/shakespeare-grave-effigy-believed-to-be-definitive-likeness [accessed 5 November 2023].

[vi] ‘‘Self-satisfied pork butcher’: Shakespeare grave effigy believed to be definitive likeness’, The Guardian.

[vii] ‘Ruffs’, The Fashion Historian, 2017, http://www.thefashionhistorian.com/2011/11/ruffs.html [accessed 5 November 2023].